For those who struggle to distinguish between trends and individuals, policies and people, a disclaimer. Being anti-immigration means being in favour of restricting immigration, not being against immigrants as people (whatever that would mean). Being against Americanization, or being in favour of anti-American Canadian nationalism, obviously does not entail a dislike of all Americans as people. Now, let’s begin.

2025 saw the reawakening of a long latent anti-American Canadian nationalism, as President Trump machine gunned us with tariffs and threatened to use “economic force” to annex us. Canadians put out flags, boycotted US products, and stopped travelling south of the border for non-essential purposes. Half of snowbirds are considering selling their US homes, and Canadian companies are seeing incredible boosts in sales numbers. Perhaps most significantly, the rubber duck museum in Point Roberts is moving to BC due to tariffs and the nosedive in Canadian tourism.

Due to a confluence of several factors, but particularly the fact that the annexation threats and tariffs began in January and early February, while Canada had a leader on the political “left” while the US had a leader on the political “right” (for whatever worth those terms have), the new Canadian nationalism was particularly strong among Liberal, NDP, and Green voters.

For this reason, Canadian news consumers were treated to quite a few podcasts and essays in which woke ideologues went to great lengths in attempting to rationalize why they were putting up a Canadian flag outside their house to celebrate a genocidal, systemically racist country which was built on unceded, stolen native land by intolerant, British “dead white males”. The pageantry of a figure like Justin Trudeau – a man who had spent the preceding decade vilifying Canadian history at every turn, even claiming that Canada is a “post-national state” with “no core identity” in a New York Times interview – becoming a red-blooded, bomb-throwing nationalist was nothing if not comedically surreal.

No matter how entertaining these shenanigans were, they revealed a deeper reality: in Canada, nationalism is not a “left” or “right” issue – it is a fundamental precondition of our existence as a sovereign nation in North America.

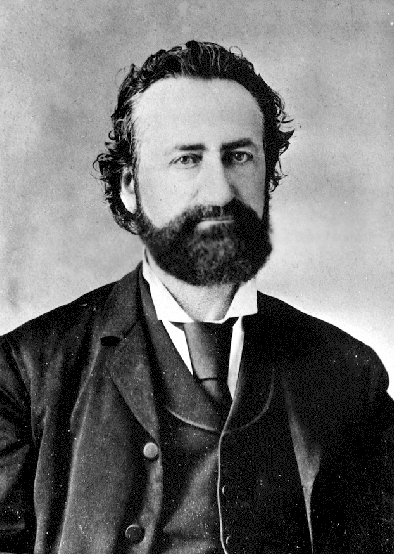

Sir John A. Macdonald, our first Prime Minister, was an anti-American Canadian nationalist. As was Robert Borden, of the $100 bill fame. So was Amor De Cosmos, the newspaperman and politician with an impeccable name and beard who bears much of the praise for bringing BC into Confederation, and who would go on to become the second Premier of that province.

So was John Diefenbaker, who stood up against US meddling and for Canada’s old time identity at every turn. So was George Grant, who wrote Lament For A Nation in 1965, after Diefenbaker was brought down in 1963 – an election fought over the stationing of American Bomarc missiles on Canadian soil, and an election in which the John F. Kennedy administration blatantly interfered to oust Diefenbaker.

So was the classic writer and humourist Stephen Leacock, who wrote Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town. So was the great poet Pauline Johnson (1861-1913). The daughter of a hereditary Mohawk chief, her Wikipedia says that she “made an indelible mark on Indigenous women’s literature and theater”. True enough, but she also wrote Canadian Born, with this as the last stanza:

“The Dutch may have their Holland, the Spaniard have his Spain,

The Yankee to the south of us must south of us remain;

For not a man dare lift a hand against the men who brag

That they were born in Canada beneath the British flag.”

If you look at the writings and speeches of most of our great historical figures, you find that they were anti-American Canadian nationalists. Is this some kind of coincidence? Far from it. From Confederation until the signing of the first Canada-US trade deal in the late 1980s, it was broadly understood that Canada’s existence as a sovereign entity was principally under threat from cultural, economic, or even military conquest by the United States. This is not surprising, given that Confederation in 1867 was only 55 years after the US invasion of Canada in 1812 – the same time difference between now and 1970.

The defense mechanism to counter this ever present threat was to create an economy that ran on an east-west axis – this was geographically improbable, but geopolitically necessary to avoid getting sucked into the continental pull of the US, a black hole into which our sovereignty could easily disappear into. The concept of a Canadian east-west axis was still strong enough in the public mind in the 1980s that John Turner could reference it at considerable length in a debate against Brian Mulroney in the 1988 free trade election:

“We built a country east and west and north. We built it on an infrastructure that deliberately resisted the continental pressure of the United States. For 120 years we’ve done it. With one signature of a pen, you’ve reversed that, thrown us into the north-south influence of the United States and will reduce us…to a colony of the United States, because when the economic levers go, the political independence is sure to follow. ”

From 1988-2025, anti-American Canadian nationalism was put on pause – we no longer needed it, because the Dominion would blissfully float into ever closer integration with the Republic. We had given them what they wanted – access to cheap Canadian resources, a market for their finished products, and the ability to buy up our companies. They would never hurt us now, right?

In 2025, we snapped out of this dreamlike trance into the harsh light of reality. Upon awakening, there was a temptation to interpret the renewal of the US threat through the lens of 2025 politics – but the truth is that this threat has always been there, and Canadians of all stripes have long recognized it. In the 1891 free trade election, Conservative John A. Macdonald fought free trade with the US, and in the 1988 free trade election, Liberal John Turner did the same.

Anti-American Canadian nationalism is an attachment to our particular corner of the earth, an affirmation of our will to remain sovereign in our affairs and to preserve our distinctive identity and institutions. In aligning myself with it, I draw on a deep and refreshing well of thought that is not in any way partisan, or even political. It is simply about survival.

Similarly with immigration. Again, here is an issue which is distorted if analyzed through the lens of 2025 politics. However, if one looks back on all the great Canadians throughout history, Conservative and Liberal, progressive and traditionalist, you are more likely than not to find they were immigration restrictionists.

Stephen Leacock, the lovable humourist? Immigration restrictionist. But surely not J.S. Woodsworth, who helped found the CCF, which was the precursor to today’s NDP? He was a restrictionist, too. So much so, that he wrote a book called Strangers Within Our Gates (try getting that published today!). The Conservative John A. Macdonald? Restrictionist. The Liberal Prime Minister Mackenzie King? Restrictionist.

But how about Amor De Cosmos, with his dapper beard and kumbaya-sounding name? Immigration restrictionist.

So, some stodgy old white men were against immigration, but surely not Canada’s historical female trailblazers! Well, Emily Murphy, Canada’s first female judge, wrote a book called The Black Candle in which she linked immigration to the drug trade (try getting that past a publisher now!). Agnes Macphail, the first woman elected to Canadian Parliament, apparently had such extreme views on racial minorities that she has been labelled a “white supremacist”. One can only imagine what she may have said about today’s open-door immigration policy.

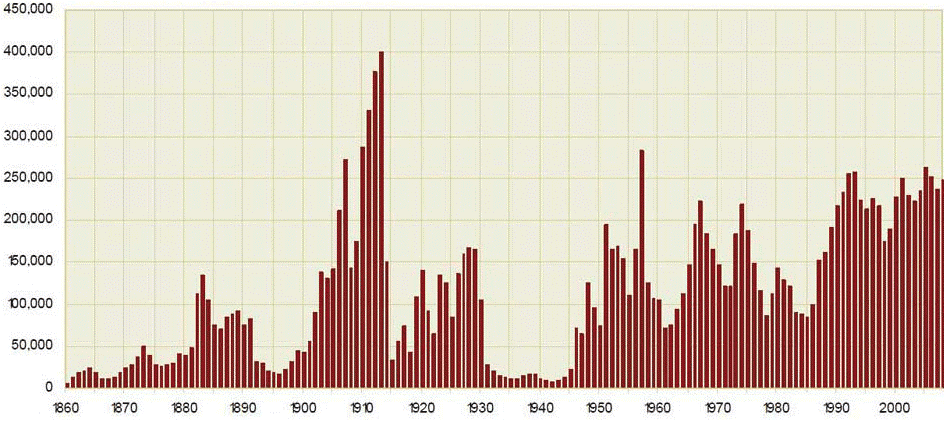

Despite the mythology that Canada is a “nation of immigrants”, an evidence-free claim that has been used throughout the Western world, even in countries like Britain, immigration has historically been viewed with intense suspicion in Canada. From Confederation until the early 1990s, we had a “tap-on, tap-off” policy, where immigration was tied to public opinion and domestic economic conditions. This resulted in several large waves interspersed with very long periods of time with almost no immigration at all, during which past arrivals were Canadianized and infrastructure of all kinds was given breathing room to catch up to population growth.

In 1990, the government of Brian Mulroney – the same government that replaced Canada’s “east-west axis” economic policy with a north-south free trade deal with the US – ended our “tap-on, tap-off” immigration policy and replaced it with a high, continual inflow regardless of either public opinion or domestic economic conditions like unemployment levels. I refer to the never-ending immigration wave that began in 1990 as

“mass immigration”, a term that encapsulates its distinctive difference from our previous immigration policy – its sheer quantity.

In this chart, you can see the peaks and troughs of the “tap-on, tap-off” policy that prevailed from 1867 onwards, and then the beginning of the permanent immigration wave in 1990:

This uninterrupted immigration wave continued under both Conservative and Liberal governments, until Justin Trudeau made a strategic error after the pandemic, one that ultimately proved fatal to the continuance of his own government – and perhaps the continuance of mass immigration itself.

His government pulled out all the stops, beavering away to scrap or weaken every possible immigration regulation, small or large, with the goal of massively increasing numbers. Why they did this remains unclear – theories abound, but no commentator actually knows for sure. It may have simply been a very clumsy attempt to avoid a recession through a population growth fuelled rise in the GDP. The answer will likely come out in a political biography of one of Trudeau’s ministers years from now.

The Trudeau immigration wave fuelled annual population growth of roughly 1.3 million in 2023, first crashing through our hospitals, walk-in clinics, housing, food banks, social services, and homeless shelters – before crashing the public’s support for the Trudeau government, and then finally destroying public support for immigration itself.

Finally, the Canadian public is beginning to question what is increasingly referred to in common parlance as “mass immigration”. The Carney government has slashed numbers, ending the post-pandemic Trudeau immigration wave and getting Canada back on track with the slower, post-1990, infinity immigration wave kickstarted by Mulroney 35 years ago. But the problem for the moneyed interests that depend on mass immigration for their business model is that this crackdown has not ended support for immigration restriction.

The Canadian people have endured a deep psychological trauma from seeing house prices and rents skyrocket, loved ones waiting for hours in crowded emergency rooms or hospital hallways, foreign workers brought in by Tim Horton’s and Canadian Tire to replace young Canadian workers, and hearing endless rumours of international students raiding food banks intended for poor Canadians. The survival of the post-1990 mass immigration model is seriously in question, with Canada’s immigration department admitting that support for immigration has fallen “to a low not seen in 30 years”.

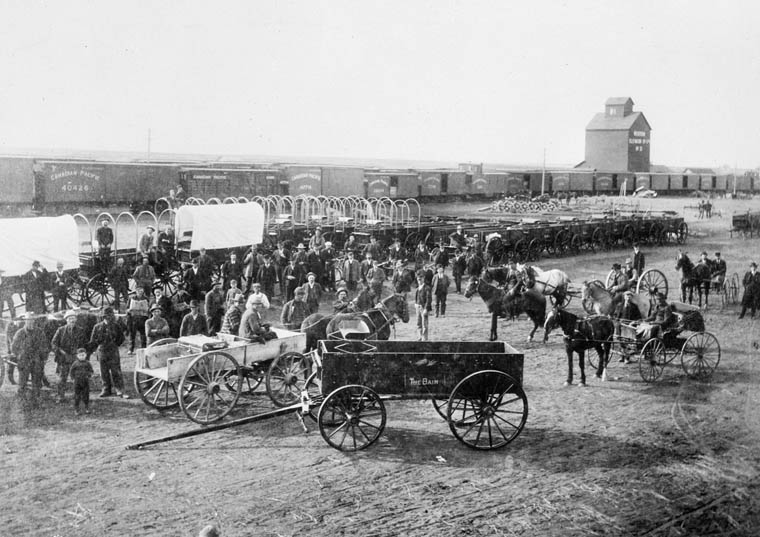

This is a welcome development. I freely admit my opposition towards not only the mass immigration policy began in 1990, but also the very need for immigration at all in a country that is no longer in a frontier stage of history in which we require the “stalwart peasants in sheepskin coats” sought out by Minister of the Interior Clifford Sifton to settle the prairies.

While unproductive sectors like real estate development do depend on infinite population growth for their parasitic business model, what case can be made from the standpoint of everyday Canadians for keeping a single immigration program? While the spousal sponsorship program should be kept for those Canadians who fall in love with non-Canadians, why not wind down every other program and reap the benefits of population stability?

At the close of 2025, we find that, through sheer flukes of historical circumstance, two great forces of nature, anti-American Canadian nationalism and immigration restrictionism, have been awakened from a decades long slumber induced by the Mulroney government in 1988 and 1990, respectively. Canadian public opinion is beginning to fold back into line with historic norms.

I align myself unreservedly with this most unlikely Canadian renaissance.

All content on this website is copyrighted, and cannot be republished or reproduced without permission.

Share this article!

Good article, but let me add a couple of things.

Diefenbaker was often erratic in his political actions as PM – he put us into NORAD in 1958 at the same time he also wanted us to develop stronger trade ties with Britain.

Generally, it was the Liberals who were more interested in continentalism than the Conservatives who were more interested in Canada being tied to or subservient to the UK, even as Liberals were strong monarchists for much of our history.

But what was missing was on Harper and the Iraq War – where in some cases, Conservatives wanted or saw Canada as merely shifting our subservience and loyalty from Britain as our protector or master to that of the US – and people like Harper saw Canada taking an independent course or rejecting the US on something like the Iraq as “disloyalty”.

Look at Jonathan Haidts’s the Righteous Mind where he describes 5 core values, and “loyalty” is a key one on the right, or at least on the right in the US… and perhaps why Republicans have become so hyper-partisan and loyal to Trump for whom loyalty is a one way street.

Getting back to Harper, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canada_and_the_Iraq_War#cite_note-Gollom-2 and the footnotes – https://web.archive.org/web/20160112062026/https://www.cbc.ca/news2/canadavotes/realitycheck/2008/10/our_own_voice_on_iraq.html

And http://25461.vws.magma.ca/admin/articles/torstar-24-03-2003c.html and it was really only in Alberta that there was strong support for Canada going to war in Iraq.

The liberals were most nationalistic from 1957 through to Turner, but after the loss in the 1988 election, Chretien went along with the neoliberalism of cutting deficits and NAFTA while still trying to be seen as not buying into those things as potential Liberal voters were still far more nationalistic than voters for the PCs or the Bloc, or even Reform.

From the Toronto Star:

OTTAWA—Jean Chrétien’s decision to stay out of the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq has met with widespread approval in this country and is backed by a majority of respondents everywhere except Alberta, according to a Star poll.

The poll, conducted for the Star and the Montreal newspaper La Presse by EKOS Research Associates, found 71 per cent of those polled backed the decision by the Liberal government, with 27 per cent registering their disapproval.

Although a clear majority of 60 per cent say they object to the military move by U.S. President George W. Bush, 35 per cent of Canadians back him, support that rose during the week and an indication that a significant number of voters in this country back Washington’s move as well as Ottawa’s decision to stay apart from it.

Chrétien’s Liberal government decided to stay out of the U.S.-led invasion because Washington could not win multilateral authorization for the war at the United Nations. But Canada still has three frigates in the region as part of a war on terrorism, leading some to suggest the government is having it both ways, winning support politically for snubbing the Americans while making some assets available to support the Americans.

Chrétien’s move, announced Monday, sparked a week of heated political debate here with the Prime Minister striving to paint his decision as an independent Canadian move while not criticizing Bush.

That was made more difficult with Wednesday’s comments by his natural resources minister, Herb Dhaliwal. He said he felt Bush failed as a statesman and let the world down, remarks he later clarified to indicate they were not a personal criticism of the U.S. president or his administration.

The NDP and the Bloc Québécois backed Chrétien, but Canadian Alliance leader Stephen Harper has thrown parliamentary nicety out the window in his attacks on the Liberals, a government he has described as “gutless and juvenile” and one he says has turned its back on Canadian values and traditions.

EKOS interviewed 720 Canadians beginning Monday, after Chrétien made his announcement and ending Thursday evening, before yesterday’s massive bombing of Baghdad and other Iraqi cities by the U.S. It says its results are considered accurate to within 3.7 percentage points, 19 times out of 20.

The poll also found almost unprecedented awareness and interest among Canadians in the war and this country’s role.

EKOS president Frank Graves said Canadian sympathy for Bush’s position rose during the week, likely because people in this country began to believe he might show restraint and try to force mass Iraqi desertions or a quick surgical strike at Saddam Hussein.

Yesterday’s strikes on the Iraqi capital may have ended any rebound Bush was receiving in public opinion in this country, Graves said.

Graves also said part of the Canadian strengthening of support for Bush’s position may have been a reaction to what voters perceived to have been some “strident antipathy” toward the Americans from Liberals, including Dhaliwal, Mississauga Centre MP Carolyn Parrish who referred to them as “bastards,” and the infamous “moron” comment from Chrétien’s former communications director, Françoise Ducros.

EKOS found the greatest support for the Liberal position in Quebec, among women, those who are university educated and who described themselves as Canadian nationalists.

Those most fervently opposed to the Chrétien position lived in Alberta, were among the country’s most affluent and overwhelmingly are Canadian Alliance and Progressive Conservative supporters.

The polar opposite positions in Alberta and Quebec are most striking, Graves said. He added frustration in Alberta may have repercussions in the future because it seems to be constantly offside on national issues, while anti-American sentiment in Quebec was the strongest EKOS has seen in 10 years.