Support for economic nationalism is sweeping this country like a prairie fire. At the time of writing, the /r/BuyCanadian subreddit has swelled to 135,000 subscribers. Prime Minister Trudeau has called for an economic boycott of American goods. Premier Ford has ordered American alcohol to be pulled from liquor stores shelves. Nova Scotia has done the same, as has British Columbia (though in B.C. this measure is so far limited to alcohol from certain Republican states). Canadians are circulating tips on social media about which which countries own which fast food chains, and which grocery store brands are American-owned.

Of course, this is all in response to the Trump administration’s unprovoked 25% tariffs that were officially announced yesterday, mere weeks after Canada sent water bombers to help extinguish the L.A. wildfires. In Canada, the sense of hurt and betrayal is palpable – the American anthem has been booed at hockey games in Ottawa, Calgary, and Vancouver, and at a Raptors game in Toronto.

Many Canadians would have boycotted American goods even if our politicians hadn’t endorsed the idea – for weeks, my small town’s community Facebook page has been abuzz with calls to buy Canadian. People want to hit back at an American administration that is seeking to inflict damage on the Canadian economy while arrogantly informing us that the only way out is to become a 51st state – the benefits of which apparently include “Much lower taxes, and far better military protection for the people of Canada – AND NO TARIFFS!”.

On social media and in everyday discussions, there is an another sentiment arising: why weren’t we focusing on buying Canadian even before this trade war? Why shouldn’t Canadian consumers incorporate some degree of national preference into their buying decisions at all times, not just when our economy is under threat?

Other questions about the fundamental orientation of the Canadian economy are also bubbling up. Wasn’t it risky to put all our eggs in one shaky basket by becoming overly dependent on selling to the American market? Is sending a stream of raw natural resources to the U.S. and receiving finished goods in return a healthy economic model for a developed country like Canada? Why shouldn’t we put more focus on value-added products? Why do we still have interprovincial trade barriers? Why shouldn’t we refine our own oil?

Answering these questions doesn’t require that we reinvent the wheel. Even a brief overview of Canadian history reveals a rich vein of economic nationalism that can be mined for enduring insights.

Sir John A. Macdonald believed that unmitigated free trade with the United States would open Canada up to commercial and political domination by our much larger neighbour – his National Policy sought to boost Canadian manufacturing through protective tariffs. In his last election in 1891, Macdonald successfully defeated the Liberals, who were running on a platform of commercial union and “unrestricted reciprocity” with the United States. Another Free Trade Election was held in 1911, in which the Conservatives under Robert Borden swept to victory on a platform that championed the National Policy, framing the issue as “whether the spirit of Canadianism or of Continentalism shall prevail on the northern half of this continent”.

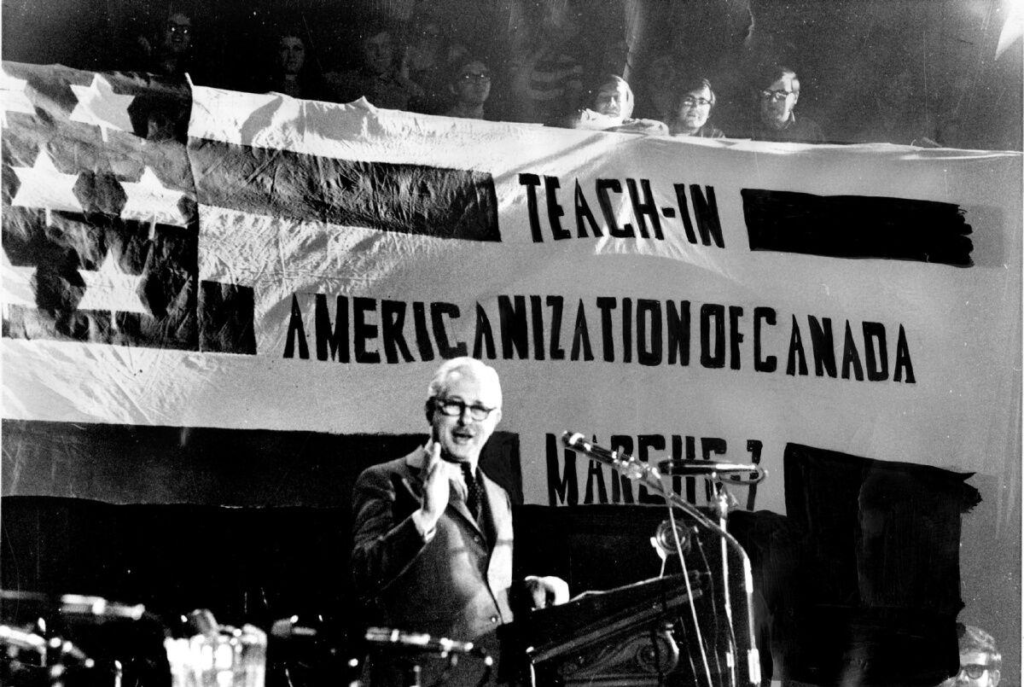

Throughout our history, many of Canada’s most prominent intellectual heavyweights were economic nationalists. Walter Gordon – considered to be the father of Canadian economic nationalism – chaired the 1957 Royal Commission on Canada’s Economic Prospects, which warned against Canada’s policy of allowing natural resources and industries to be acquired by American business interests. The sometimes gloomy but always prescient philosopher George Grant saw the all-consuming continental pull of the United States as a threat to Canada’s historic identity, and later in life came to perceive the U.S. as “the source of the technological dynamism that dissolved all particularities in the name of a homogeneous” global order.

Perhaps most relevant to the current Canada-U.S. trade war is Harold Innis. His intellectual disciple Marshall McLuhan lamented Innis’s premature death in the early 1950s as a loss to humanity because of his immense contributions to various disciplines including communications theory. Innis was “resolutely anti-American” and “believed that continentalism and American foreign policy in the world at large were imperialistic”. He was concerned with how Canada could best “sustain and advance its political independence” with such a neighbour.

Innis saw Canada as a kind of organic entity stretching from East to West. This East-West axis conception of Canada is particularly relevant in today’s context, in which Canada is scrambling to come up with economic alternatives to dependence on the U.S., a country which has of late proven itself to be a particularly unreliable and volatile trading partner – to say the least. Imagining ourselves as a nation stretching along an East-West axis is a conceptual alternative to total dependence on our neighbour to the South. The most obvious policy conclusion stemming from this view of Canada would be to abolish the interprovincial trade barriers that are hampering our national cohesion and prosperity.

In her weekly Good Sunday Morning! newsletter earlier today, Green Party Leader Elizabeth May called for scrapping these pesky domestic trade barriers, and went on to outline an economic vision wherein Canada is less dependent on the United States:

“We need to be unafraid, resilient and fair. The bully will be surprised if we refuse to panic. Let’s hope we can use this crisis to make real changes to our fragmented federation- eliminate interprovincial trade barriers, emerge with an economy based, not on a rip and strip model of resources exported without value added, moving to a circular economy, with greater resilience and self-sufficiency.

The meek will inherit the earth, but first we have to organize.

And not be so meek. We are Canadian, As we topple the bullies, I will not mind if we pause to say, “sorry.”

Economic nationalism doesn’t mean not trading – it means trading prudently and wisely, in a way that ensures the well being of our land and our fellow citizens. It means standing up for ourselves. And in our unique context as Canadians, it means not becoming overly reliant on the increasingly politically unstable country to our South that has elected an administration willing to gleefully toss aside its strongest ally and friend for cheap political points.

In this frightening time, Canadians must band together and draw on our rich political and intellectual history of economic nationalism to boldly envision a new future in which we are prosperous, independent, and sovereign.

Editor’s note: When Canadian writer Brian Graff realized there was no digital version of Walter Gordon’s “Whither Canada: Satellite or Independent Nation” speech, he used OCR to make it available for Canadians to read on Dominion Review. Here is the speech in full.

All content on this website is copyrighted, and cannot be republished or reproduced without permission.

Share this article!

The truth does not fear investigation.

You can help support Dominion Review!

Dominion Review is entirely funded by readers. I am proud to publish hard-hitting columns and in-depth journalism with no paywall, no government grants, and no deference to political correctness and prevailing orthodoxies. If you appreciate this publication and want to help it grow and provide novel and dissenting perspectives to more Canadians, consider subscribing on Patreon for $5/month.

- Riley Donovan, editor