I grew up in Don Mills in the 1960s and 1970s, and frankly I feel lucky to have gone to school in those years, and not today. The education I got through the North York School Board was pretty good for the times. In my high school, they had some really great teachers and a wide variety of courses that I understand are no longer common (shop, home economics, music, art, theatre arts, etc.). I even took a course called “Terminal Latin” (which makes it sound like Latin is a disease, but was actually because this version didn’t lead to a second year). I was also exposed to things like Plato’s Republic, which I had to read a second time in university!

The idea of “philosopher kings” that comes out of Socrates and Plato’s Republic has stuck with me, even though I forgot most of the book and had to use Wikipedia for a bit of a refresher of the book’s contents.

Anyway, there was a recent announcement that the Liberal government was going to change the rules on citizenship to conform to a recent court ruling that invoked our Charter of Rights and Freedoms. This controversial policy change is not the only one driven by a court ruling. Like so many others, this makes me feel that the idea of philosopher kings has partly come true in Canada and the US – though this is not as positive as the original conception envisioned it to be.

Both Canada and the US are liberal democracies with fundamental rights enshrined in our Constitutions. This was done to ensure that government does not violate those basic rights. In particular, the goal was that democratically elected governments do not violate the rights of minorities even in cases where it might be popular with voters to do so. In a democracy, majorities should be able to look out for their own interests via elections, but for minorities this is an uphill battle.

Republican politicians in the US have often complained of “liberal activist judges” when it comes to issues such as abortion – though in the case of Roe v. Wade, most of the judges supporting the ruling were Republican appointees. Americans on the left have complained about the Citizens United decision that gave corporations unlimited rights to spend on elections on the basis that spending money is a form of free speech. The Heller decision re-interpreted the Second Amendment after 200 years to give gun rights to individuals, when it was originally meant to ensure that states could be free to raise regulated and armed militias, if needed.

When the Canadian Constitution was being repatriated over 40 years ago, there were concerns that the Charter would give too much power to our courts. This is turning out to be true.

We end up with Canada having three levels of government: a federal government (essentially Parliament and the prime minister, given that the head of state and senate are ineffective), the provinces and territories, and then 9 members of the Supreme Court – who have power, and are not accountable, but limit the powers of everyone else.

Philosopher kings were supposed to be “intelligent, reliable, and willing to lead a simple life” and “disinterested persons who rule not for their personal enjoyment but for the good of the city-state”. They also “understand the corrupting effect of greed and own no property and receive no salary” – though of course the reality is that in a modern society anyone old enough to sit on a court or take a leadership role will have a family and personal life and need material things and their future financial security assured.

We have seen (or are seeing) that many US Supreme Court judges do not live up to this standard. In particular, Clarence Thomas has been criticized for complaining that his salary is too low and for accepting lavish gifts (travel, vacations, a bus-sized motor home). The US process has also become highly politicized. It used to be that 60 Senate votes were required for confirmation, meaning that people chosen to sit on the court needed bi-partisan support so could not be seen as too ideological. Mitch McConnell reduced this to a mere 51 votes, so that in effect new judges can be quite ideological or biased. On abortion and other controversial issues, nominees in the US have either ducked answering questions or even misled the Senate when stating that they would respect long standing Supreme Court precedent, and then quickly overturned them once appointed.

Canada’s process of picking judges is not particularly politicized, though Stephen Harper tried to short circuit the consultation process when he was PM. But let’s assume for the sake of argument that in future, members of our court are still not chosen to skew the institution to the far left or right.

Judges are experts on the law, and nearly all come to the court from the legal community and having previously served as judges on Canadian courts, though there is no requirement to have experience as a judge. There are “conventions” meant to balance the court regionally and ensure some judges are licensed in Quebec. This is because Quebec’s civil law system is not the same British based “common law” used in the rest of the country. But let’s assume these conventions are not an issue in future.

The real problem I see is that the “philosopher kings” come from the legal community where debates on law and justice are often isolated from the wider public debates. This is the same in any profession. In architecture, for example, what professionals think might be quite removed from public tastes and opinions about design.

Lawyers and judges tend to be experts in a narrow field, or experts in narrow area of legal practice and might not understand things like economics, finance, or the sciences.

Essentially, court rulings on the Charter are judges saying “no” to elected governments – that elected governments stepped over the line in passing a law or regulation, or in the way they implemented the law.

When judges say “no”, they rarely say exactly what would actually result in a “yes”. Judges do not have to work out the specifics on laws such as legalizing marijuana, medically assisted suicide, or interprovincial trade issues.

Supreme Court rulings can often be completely out of touch with public opinion, and effectively rule out most of the solutions to an important issue, but the Court essentially can “pass the buck” to elected politicians to work out solutions that are both practical and that voters will tolerate.

On the issue of immigration, Canada accepts dual or triple citizenship (or more) with no restrictions, and this is not true of many countries. There is also the situation with “birthright citizenship”.

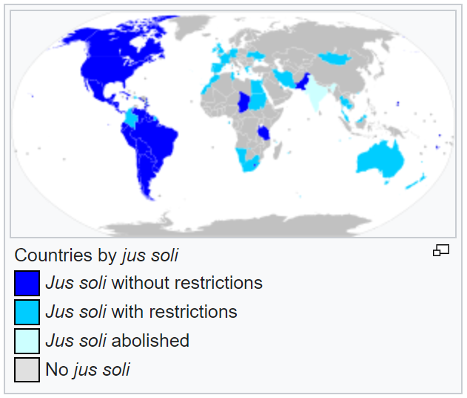

‘Jus soli’, meaning ‘right of the soil’, is the proper term for what we commonly call birthright citizenship. It means that essentially any baby born within the territorial limits of a country can claim citizenship. It is most commonly found in North and South America, including Canada and the US, while it is rare in Asia, Africa and Europe. Some countries have partial birthright citizenship. This map shows where different countries stand:

Of course, since 1492, countries in the Americas were colonized and had massive influxes of tourists and little ability to limit or stop them, and often poor record keeping. These countries, including Canada, wanted high immigration to provide labour for agriculture, then later for industrialization. Transportation across the oceans was expensive and often risky, so not many people moved back and forth across the oceans except sailors, the rich, and various elites.

Canada wanted high population growth after 1867 to maintain its independence and economic viability – and specifically, to make sure that the areas west of the Great Lakes did not end up being lost to the US. Birthright citizenship fit into this objective (though of course in addition to fears of the US, Canadian governments were afraid that British Columbia and western Canada not experience large influxes of people from Asia).

With the dawn of the jet age 60 years ago, Canada began to experience tourism from places other than the US or the British Isles. People started to fly to Canada on tourist visas, and then in the last few decades the issue of “Anchor Babies” started to be reported in the Canadian media. In theses cases, women intentionally come to Canada to give birth here so the child can have Canadian citizenship. I knew once such woman myself in the 1990s – she overstayed her visa and lived with her cousin.

In the 1985 Singh decision, Canada’s Supreme court ruled that the Charter applies to “everyone” physically present in Canada – not just citizens or landed immigrants. Of course, the Charter never said this, but because of this decision, in effect the Charter applies to asylum seekers and even illegal immigrants. The Court usually takes a broad view of Charter rights even if the Charter is silent.

The recent Bjorkquist et al. v. Attorney General of Canada decision similarly expands rights not explicitly found in the Charter – but specifically in relation to citizenship. This relates to a 2008 Harper government action, Bill 37, that is alleged to have created two classes of citizenship:

“Its effect is to prohibit Canadian citizens born abroad from passing Canadian citizenship on to their children automatically if their children are also born abroad. There is no mechanism to remove this limitation from the citizenship status of Canadian citizens born abroad to Canadian-born parents. The parties refer to this effect as the “second-generation cut-off…”

The government argued there is no right to citizenship. Nor does the Charter mention a parental right to pass on citizenship. Despite this, the Liberal government chose not to appeal the December 2023 Ontario court decision, but to change the law.

Canadians are not tied together by blood, language, ethnicity, or religion – but by ties to the land, or having been here as a part of Canadian society. The rules on passing on citizenship have changed several times since Canadian citizenship was legally created in the 1947 Citizenship Act. The issue in this Court case was that the first generation of kids born outside of Canada had more rights than their kids – though is there to be no limit?

The Charter says “Section 6(1) provides that “[e]very citizen of Canada has the right to enter, remain in and leave Canada”. The Court’s argument in this case is that this right is infringed for “the first generation born abroad, because it attaches a penalty to their choice to pursue opportunities to work and study internationally and, in the course of doing so, have children”.

Section 15 of the Charter relates to people getting equal treatment, which the Court also thought was being violated.

Canada also signs various international treaties, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the Court used this in coming up with the following:

“[181] From these decisions, I take the following principles:

a. Section 6(1) includes the right to enter, remain in, and leave Canada.

b. One purpose of s. 6(1) is to ensure that citizens have the right to have rights in their country of citizenship. This purpose grew out of the terrible rights violations of the Second World War, and can be understood to include a component of safety and security, allowing a Canadian the right to enter, remain in, or leave Canada, to ensure they can protect themselves and their rights.

c. Another purpose of the international mobility rights in s. 6(1) is to guarantee the freedom of Canadians to travel and to earn a livelihood in the global economy, and to fulfill their personal, professional, leisure and family needs. Thus, s. 6(1) recognizes and protects the individual’s choice to enter, remain in, or leave Canada, in the context of the individual’s legitimate pursuits in an increasingly globalized world.

d. Any restriction on the mobility rights in s. 6(1) that is unreasonable, unrealistic, and impractical will violate s. 6(1) and must be justified in accordance with s. 1 of the Charter.”

The problem is that many people live outside of Canada purely by choice after they have retired or because they have links to other countries – much as Canada had to help people with Canadian passports stuck in Lebanon when civil war returned to that country.

The Liberals are calling people “Lost Canadians” (“those who lost or never acquired citizenship due to certain outdated provisions of former citizenship legislation”). Instead of appealing, the remedy the Liberals are introducing in Bill 71 is to “restore” citizenship to people who “would have been a citizen were it not for the first-generation limit”.

In future, the rule will be to “demonstrate a substantial connection to Canada, a Canadian parent who was born abroad would need to have a cumulative 1,095 days of physical presence in Canada before the birth or adoption of the child”.

Note that 1,095 days is 3 years, which is what is needed now for landed immigrants to apply for citizenship, which the Liberals themselves reduced from 4 years. Only 12 countries out of the roughly 200 that exist require 3 years or less, while countries like Switzerland, Spain, Poland and Italy require 10 years, and some countries require 30 years or more.

A person could meet the 3 years by coming to Canada and getting a university degree, and then never return.

Now, had the government appealed to the Supreme Court and lost, it could have invoked the notorious “notwithstanding clause” to exempt the rules from this ruling. The idea of the notwithstanding clause was that it would carry such a stigma to use it, that it would rarely if ever be used. But Pierre Poilievre is threatening to use it if elected. Doug Ford has used the clause but then reversed it, and other premiers have also shown a willingness to propose its use.

Several potential trends or options exist – the future depends on which road we take by choice or by default.

If the notwithstanding clause is invoked a few times without a huge backlash, there is the risk that the stigma is eroded over time to the point where the Charter is toothless. Judges in Canadian courts risk provoking this situation if they continue to apply the Charter in ways that interpret it broadly. Governments may feel they have no alternative but to invoke the notwithstanding clause, and much of the electorate may simply acquiesce to its frequent and constantly increasing use.

What would be particularly problematic is the fact that the notwithstanding clause needs to be renewed within five years. It might be that a government of one political stripe enacts the clause for one or more laws, then after an election, the next government has to renew the clause. The next government might even decide to reverse the clause. We would end up with a country where parts of the Charter end up being intermittently in force on key issues. This would be chaotic.

Another alternative future is that governments start to “pack the court” by making increasingly political appointments to our highest courts and the Supreme Court itself, along the lines of the US.

In 2014, Stephen Harper tried to appoint Marc Nadon to the Supreme Court by including his appointment in a Budget Bill. The Supreme Court ruled this to be unconstitutional, but partisan or ideological judicial appointments could be achieved in future if the issue was approached more carefully than Harper’s clumsy attempt. Unlike the US, there is no requirement for any confirmation process by the Senate or even Parliament, nor is it likely that the Constitution will be amended to add any checks and balances.

Another alternative is that Canada becomes increasingly hard to govern because of regionalism (particularly in regards to Quebec) combined with a disproportionately powerful and unaccountable court system. Decisions on major issues would ping-pong back and forth between Parliament and the Supreme Court, to the point that it would take years to implement policies.

The last alternative is that Prime Ministers make a point of choosing judges who believe in limited powers for courts, narrower interpretations of Charter rights, and greater deference to Parliament. This is unlikely to happen unless voters themselves demand that the balance of power should shift from the Courts and back to Parliament.

The real problem is that Parliament itself has such a bad reputation. This is not only because of the stage managed idiocy of Question Period, but because many Canadians view Parliament as being irrelevant. Over time, Canada has become an elected dictatorship with power centralized in the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) and nearly all Parliamentary votes being “whipped” – with only the occasional private member’s bill being an exception in cases where the PM and other party leaders all agree to a free vote.

For Canada to remain a democracy we are proud of and one that works, we need to combine reforms to Parliament and our political processes with getting the courts to voluntarily limit their role and defer more to Parliament. The alternative outcomes are less effective federal and provincial governments, a Charter of Rights that is circumvented, or more US style partisan court appointments. I don’t believe that lawyers, judges, or politicians – let alone average Canadians – would prefer those outcomes.

All content on this website is copyrighted, and cannot be republished or reproduced without permission.

Share this article!

The truth does not fear investigation.

You can help support Dominion Review!

Dominion Review is entirely funded by readers. I am proud to publish hard-hitting columns and in-depth journalism with no paywall, no government grants, and no deference to political correctness and prevailing orthodoxies. If you appreciate this publication and want to help it grow and provide novel and dissenting perspectives to more Canadians, consider subscribing on Patreon for $5/month.

- Riley Donovan, editor