When I go on X, or Twitter, or Ex-Twitter or X-Twitter, my feed is often full of ideological people pushing the idea that Land Value Taxes (LVTs) are the solution to many of the problems of modern life, and the housing crisis in particular. I don’t agree, and I find these people naïve.

The idea behind land value taxes is that taxing land alone, without taxing the buildings and improvements, will mean more density. Supposedly more density will lower rents, and more efficient land use will provide other benefits.

A library book on urbanism that I am currently reading goes into the subject of land value taxes, and the origins of this idea, which go back to American political economist and journalist Henry George (1839-1897). The book sees high land-only taxes as a means to reduce land prices by eliminating the land speculation that pushes up prices.

There are many problems with land value taxes – including how to fairly land value to begin with. Property values are complex – they involve leases and other factors, rather than just taking the total value and deducting for the estimated value of the physical building alone. For on thing, some buildings cost far more to demolish than they are worth!

Taxing land does not actually make housing affordable. Reformers 100 years ago in Vienna took the approach of using land taxes to both drive down land prices and provide money to build publicly owned housing with fair rents. That is separate, however, from setting rents based on income – which is what public housing in Canada and the US initially did to help people with low incomes who were paying more than 30% of their income in rent.

It occurred to me that land taxes alone fail to actually help people who need help the most, or who lack an adequate income to pay for necessities. Housing is a necessity – though whether or not we define housing as a basic human right is another question that has been in the news lately.

We have a mixed economy – and this is unlikely to change. The communist/socialist ideal of government doing nearly everything is not going to happen, nor will some libertarian vision of leaving everything to the market (and that vision doesn’t address how those too old or sick to work would manage to pay for necessities).

Most “affordable” housing programs Canadian governments have funded since the 1960s essentially require subsidies to cover the difference between the cost of housing (rent) and what people supposedly can afford (30% of income). These programs, however, only help a small percentage of people in need. The waiting lists in Toronto are decades long, and this is likely true of other major Canadian cities.

Generally, the issue of housing affordability is an urban issue, since rents are higher in cities. In the book I am reading, this is attributed to land prices, though certainly the problem in Canada is also that major cities have high population growth from immigration.

In the case of Toronto and Ontario in general, people from “have not” regions of the country (Atlantic provinces and some of the Western ones, in addition to the flight of Anglos from Quebec) used to migrate to Ontario and its bigger cities. But the flow is now reversed, with Ontario and B.C. seeing far more people leave than come in from the rest of the country.

In the end, we have two choices. First, we can subsidize things like housing – directly with vouchers paid to low-income tenants, or indirectly by lowering rent for some people through government subsidies. Secondly, we could implement a Universal Basic Income (UBI), which also has other names like “Guaranteed Income”, and then let people choose how to spend that money themselves. Even with UBI, rent controls or other policies may still be needed to protect tenants.

The problem with implementing UBI is that rents are higher in the cities. While rents are high in Canada’s biggest cities, like Toronto and Vancouver, the cost of nearly everything else is lower. Some people can walk or bike to nearly everything, and use public transit only rarely. Nearly everything that is available to buy can be found in big cities, and there is often price competition. People in rural or remote areas often cannot get things, face high prices due to lack of competition, or have to pay high transportation costs to have things shipped in. Worse, people in remote areas often have to fly or drive long distances for medical care. In Northern Canada, not only are rents high, but the price of nearly everything is high – since it has to be flown in at huge cost to maintain a “Southern” or Western lifestyle.

So how can things be “fair” in such a huge country when it comes to subsidies or giving people more money to live on?

In theory, Canadians are free to move to where they want to live and balance the cost of living against other factors. But reality is different.

Should we encourage or force people living in the North to move to the South, or continue to provide high subsidies to the far North, which only encourages more people to live there? When someone moves into affordable housing where the rent is 30% of income, they will likely lose that if they want to move somewhere else – current programs discourage people from moving to where they might have a better job or otherwise be better off (closer to family, etc.).

This brings us to a fundamental question – what should we subsidize? Of course, answering this question also means deciding what we should not subsidize.

For around 300 years, governments have provided free education to children – now including high school. This was not socialism. The justification was that education and literacy are necessities, and children should not be denied education merely because their parents cannot afford it, or because their parents are too selfish or unwilling to educate their kids.

Since World War Two, Canadian governments have finally had to accept that subsidizing basic health care is necessary. The government has accepted that it is unjust to not provide hospitalization or medical care to people who are unfortunate enough to become ill or get cancer, or who manage to live long enough to suffer from the maladies or physical decline of old age. This includes paying for people who injure themselves through their own stupidity or risk taking.

At the other extreme, we have the federal and Ontario governments providing billions of dollars in subsidies to wealthy multinational corporations to make electric vehicle (EV) batteries or other goods. This is because other jurisdictions are offering subsidies nearly as generous. These subsidies are needed to get investment that in theory will be a net economic benefit to the country, and generate wealth needed to pay for health care, education, infrastructure, and so on. In that sense, these “subsidies” are more akin to an investment that should pay dividends in the long run.

Between the extremes of clearly justifiable spending on basic health and education at one end, and spending that is more like an investment that should pay for itself but is highly speculative, are endless other types of government spending. There are forms of subsidies to individuals, farmers, businesses, non-profits, other governments, and so on. Some of these subsidies are pure “pork”, or done for dubious political reasons.

Getting back to land value taxes, land prices are higher in cities and of course that will be reflected in residential rents. But do people have a right to live in the city they want?

Many of the people currently on lists for subsidized housing are not working, or are working minimum wage jobs. Would it not make more sense just to pay the cost for them to move to a city where there is currently cheap rental housing available? Or maybe we should build affordable housing in cities where land and construction costs are cheaper, and force people to move to the new housing. If they won’t move, we could take them off the subsidized housing list (or move them back to the bottom of the list).

Apart from the fact that people have family and friends in the city where they are living now – which might mean that forcing people to move would be seen as cruel – why shouldn’t people be encouraged to move to where housing is cheaper?

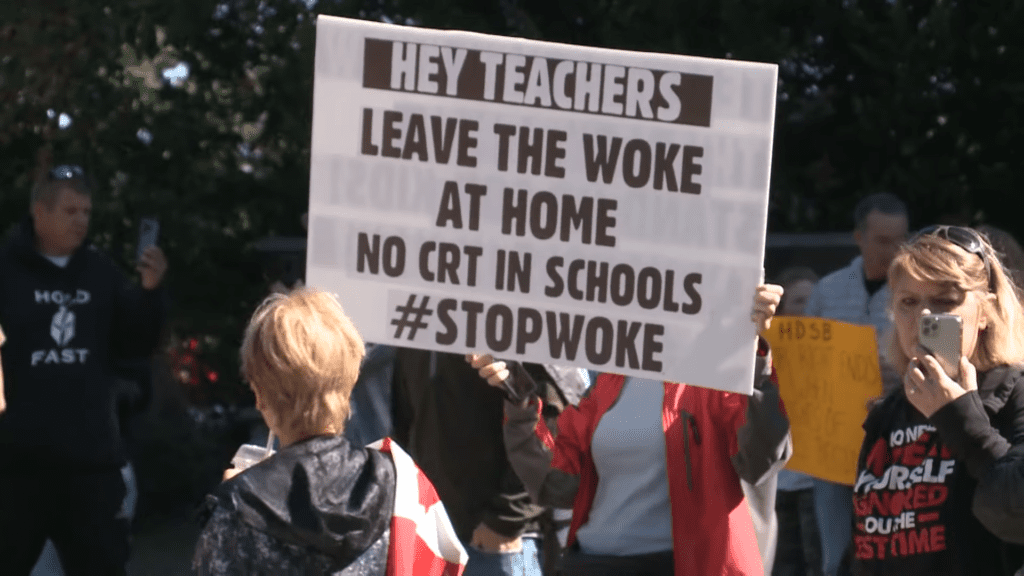

Canada has an insanely high level of immigration, in both permanent and non-permanent admissions. Nearly all of the people in these categories enter the country through a handful of international airports that are located, not coincidentally, beside our biggest cities with the highest rents! Yet, we do not force immigrants to move to smaller cities where the rents are cheaper, and the unemployment rate might actually be lower.

Increasingly though, new or recent immigrants are settling outside of Canada’s three largest cities because of high rents and the lack of opportunities if they stay. This, however, is by chance and not by a government policy that requires people to settle where labour is most needed before they have the right to remain in Canada.

Another problem with land value taxes is that in general, cities have been the major drivers of wealth creation in modern times. Small cities have grown and become large ones because land was not so expensive as to discourage businesses from settling or staying in a city. It is unlikely that land value taxes would only apply to residential uses and not to all uses – including industrial buildings that take up large areas of land and that cannot be densified.

Think of Detroit for example, which was a very small city until the American auto industry took off at the start of the 20th century. There is a huge economic advantage to businesses in the same industry clustering together, and land value taxes would likely mean that industries and good jobs would disperse instead of clustering. The Detroit of today is a different matter, since it has so much underutilized residential land available. Instead of a land value tax, it would make far more sense just to delay tax increases for a significant period of time to encourage redevelopment.

There are some general “rules” about taxes that apply to subsidies as well. Taxes are supposed to be levied on things you want to discourage. Of course, we often view subsidies as being a tax reduction or incentive to encourage things we want. There is also the idea of “user pay”, the concept that those who benefit from government spending should cover the costs of the things that benefit them – though sometimes “user fees” or other attempts at cost recovery go too far.

There is also a problem of fairness – that poor people should not subsidize people who are richer than them. “Equity” is another word for fairness. In one way of looking at it, there are two types of equity – “vertical equity” and “horizontal equity”.

Vertical equity is the rich versus poor type of fairness. We have progressive taxation to get more vertical equity. People who advocate a “flat income tax” think it would be fair if everyone paid the same tax rate, such as a 10% flat tax on income. The problem is that taxing someone making $1 million a year at 15% is not as painful as taxing someone making $20,000 a year at 15%. The rich person is still fabulously wealthy at $850,000 a year, while someone making $20,000 a year losing $3,000 means that they will not be able to pay for necessities like food and rent.

Horizontal equity is trying to provide fairness to people in roughly equal situations – such as two university students from families with similar incomes getting the same grants and paying the same tuition. A big problem with programs designed to deal with housing is that a few people get a big benefit, while most people who have the same level of need get nothing, or will only get help in the distant future once they have moved up the long waiting lists for subsidized housing.

Related to the above is that often people in the middle class, who feel they work hard and do not have an easy time with their family finances, believe that their taxes are going to help people with lower incomes get subsidies that end up making the lower income family better off than the middle class one.

An example of this might be a two-income family making $80,000 a year and paying high “market” rents. They live next to a one-income family making $50,000 a year – by choice, only one spouse in this family is working. Assume both families are paying $2,000 in monthly rent, or $24,000 a year, which is 30% of $80,000 for the two-income family. But 30% of $50,000 is $15,000, so if the one-income family gets a $9,000 rent subsidy on top of the benefit of having a stay-at-home spouse, who can blame the “richer” two-income couple from feeling that subsidies are unfair?

But the same unfairness may be true of a young couple living in small city who pay taxes and $15,000 a year in rent. They may perhaps like to move to the bigger city for better job opportunities, but cannot afford it as they would be lucky to even find an apartment as cheap as $24,000 a year!

We have people suggesting that students training to be doctors and nurses should get a break and pay no tuition, but this also seems unfair. It is unfair to young people who do not go to college and university, when we already subsidize post-secondary education. It is unfair to students who take other courses, like dentists or lab technicians or other jobs related to health – let alone other fields of study. And then of course after graduation, doctors and nurses will make more money than many other degrees or diplomas, and yet not have to pay more taxes than anyone else.

Worse still, if we provided free tuition to people studying to become a doctor or nurse on top of current subsidies, there is nothing to stop the people who graduate from moving to another province. Worse yet, they may move to the US or some other country where they will not pay taxes back into our system to pay for their education or educating someone else to replace them. Unlike the US, non-resident Canadians are not required to file and pay Canadian income taxes, if they have done the minimum to break ties with Canada (like not owning a home here).

Many other subsidies we pay make little economic sense, but we do them for other reasons. Daycare is expensive, and governments are subsidizing it even if the parent who is able to work as a result earns only minimum wage. In this situation, it would be cheaper and better for everyone to provide a smaller break for them to stay at home and raise their own child until school age. People do not object to the seeming waste of this scenario because we want to encourage women to stay in the workforce and return to work quickly if they have a child. Some subsidies are taken as justifiable in the name of broader social goals or imperatives, even if they seem economically inefficient.

Tax breaks and subsidies are essentially the same thing. Stephen Harper was notorious for inserting into budgets various tax credits designed to pander to voters, like the ”Children’s Sports and Arts Tax Credit”.

Returning to housing, the last two years have seen governments at all three levels spending massive amounts of money to deal with the housing crisis. This has included direct subsidies to build housing, low-interest rate loans, the sale of land for housing well below market value, and exemptions on development charges or other taxes in order to provide an incentive to get housing built.

All of this was happening at the same time that the Bank of Canada raised interest rates to fight inflation because of an overheated economy. Of course, the high interest rates meant higher mortgage rates, which more than offset the subsidies and incentives intended to increase housing supply and/or make housing cheaper.

All that those housing-related subsidies are doing is trying to mitigate the impact of Canada’s policy of not only doubling permanent immigration from 250,000 to 500,000 since 2015, but also the out-of-control foreign worker and international student streams that have pushed our population to around 41.5 million.

The programs and subsidies directed towards housing would have been unnecessary had immigration been kept at Harper era levels – though even under Harper housing affordability was an issue, and the problem has been escalating since the early 2000’s.

This is the real problem with subsidies – when one government policy is diametrically opposed or contrary to some other government policy. Subsidies are not providing any net benefit, but just cancelling out something else that the government is doing.

In the case of housing, this was an immigration policy driven by the interests of big business and the banks, resulting in an approach that was skewed toward specific interests over the interests of Canada as a whole.

All content on this website is copyrighted, and cannot be republished or reproduced without permission.

Share this article!

The truth does not fear investigation.

You can help support Dominion Review!

Dominion Review is entirely funded by readers. I am proud to publish hard-hitting columns and in-depth journalism with no paywall, no government grants, and no deference to political correctness and prevailing orthodoxies. If you appreciate this publication and want to help it grow and provide novel and dissenting perspectives to more Canadians, consider subscribing on Patreon for $5/month.

- Riley Donovan, editor