Another day, another op-ed in a major newspaper criticizing the Trudeau government’s immigration policy.

Even just a year ago, such pieces were few and far between. It turns out there’s nothing like raising immigration to a net annual rate of 1.273 million to blow wind into the sails of the immigration restriction movement.

Before I go on, a net annual immigration rate of 1.273 million is impossible to visualize, so briefly consider this: a million is one thousand thousands, and a year is 365 days. Dizzying.

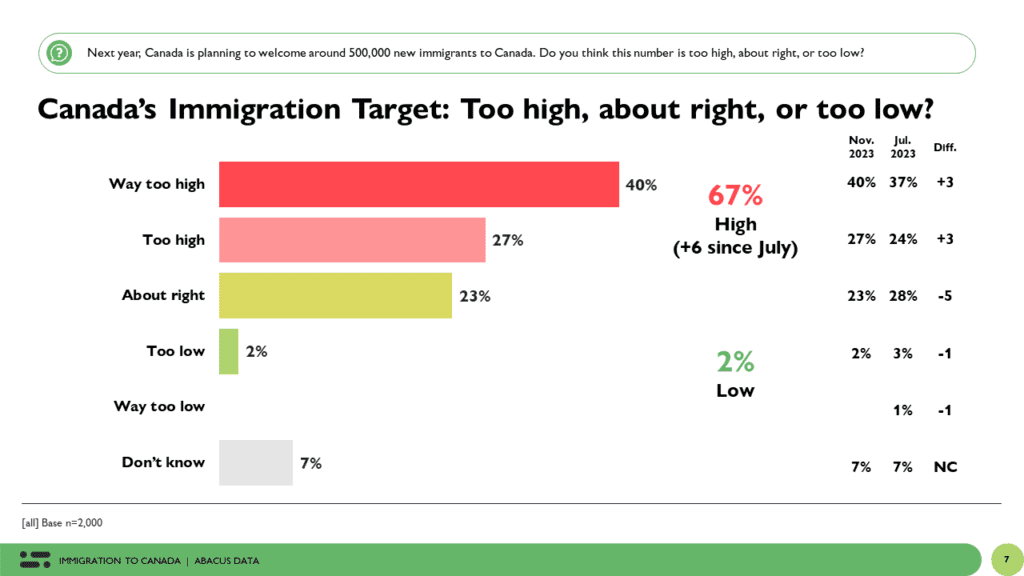

When you put it that way, it’s easy to see why the immigration-skeptic op-eds are coming thick and fast at last, and why immigration is now in the list of top five most important issues for Canadian voters.

On to the latest expression of immigration skepticism. In a column for the National Post earlier this week, prominent political analyst Tasha Kheiriddin argues that massive immigration-driven population growth in English Canada is fuelling the rise of separatism because of fears over Quebec’s declining share of the national population.

In 1961, Quebec’s share of the Canadian population was nearly 29%. Today, it is a little over 22%. As this share continues to drop, some in the province are worrying that what was once a partner in Confederation will be reduced to a thoroughly irrelevant backwater. Still visited by Anglos on school field trips, perhaps, but a dwindling and increasingly ignored voice in Parliament.

As Parti Quebecois leader St-Pierre Plamondon, who is calling for a third sovereignty referendum, puts it:

“Either we choose to raise our immigration thresholds to between 120,000 and 150,000 per year to try to maintain Quebec’s proportion (of immigration to Canada), which means the decline of the French language and an acute housing crisis, … or we choose thresholds based on our capacity to receive, which means a significant drop in Quebec’s political weight in Canada, possibly below 15 per cent…”

This is an impossibly hard choice to force our fellow countrymen to make.

Under the Canada-Quebec Accord of 1991, Quebec was granted a considerable – though not total – degree of control over immigration. While Quebec won control over the selection of economic immigrants – and thus can determine the overall volume of new permanent residents accepted – Ottawa retains control over family reunification, refugees, and most temporary immigrants.

To preserve its language and culture, Quebec has historically kept permanent resident volumes relatively low. Had the rate of immigration-driven population growth in the rest of the country not grown so dramatically in recent years, Quebec’s choice of low immigration would have posed no significant problems. Alas, Quebec now finds itself between a rock and a hard place.

As huge numbers of immigrants bolster English Canada’s political weight, La Belle Province has to choose between putting its distinctive identity at risk by adopting the same open-door immigration policy as the rest of Canada, or fading into irrelevance on the national stage. They have been dealt a shady hand from a dealer they were already suspicious of, and it’s hard to blame those Quebecers who would rather walk away from the table entirely.

Quebec Premier François Legault is opposed to holding another sovereignty referendum, but has not ruled out a referendum on giving total control – instead of the current partial control – over immigration to Quebec. Again, a referendum of this nature would have been entirely unnecessary had federal immigration numbers simply not increased to such ludicrous heights.

While obtaining complete control over immigration would make it easier for Quebec to protect its language and culture, it would not solve the important issue of Quebec’s shrinking political weight in Confederation. This can only be solved by the Bloc Quebecois becoming laser-focused on wielding its influence in the House of Commons to push for federal immigration numbers to come down, rather than pursuing distracting theatrics such as the motion for Canada to sever ties with the monarchy.

Both English and French Canadians now have yet another reason to push back against the policy of large-scale immigration embraced by the country’s out of touch political and media elite: immigration-driven population growth is creating unnecessary tension within our Confederation. In case you want even more reasons, I drew up a list of ten.

I will close with a concluding thought on a particularly unhelpful aspect of Canada’s immigration discussion.

Concerns over the erosion of Quebec’s identity as a result of high immigration are widely treated as legitimate by Canada’s political elite. Sometimes, as in the case of their secularism bill barring police and teachers from wearing religious symbols (read: hijabs), Quebec is criticized by columnists in English Canadian media and politicians in Ottawa for going too far in the defence of its identity – but the fundamental idea that Quebec has the right to defend its identity is taken for granted. As it should be. Something of real and immeasurable value would be lost if the four-hundred-year-old culture of the last French-speaking region of North America was displaced because corporate interests convinced Canadians that it’s crucial to raise our GDP through endless immigration.

Concern over the erosion of English Canadian identity by large-scale immigration, however, is ignored entirely by Canada’s political class and the mainstream media. The defence of English Canadian culture is not generally criticized for going too far, because the very existence of a distinctive English Canadian identity is simply dismissed.

Some readers may know that I live on Salt Spring Island, a rocky hazard to navigation in the Strait of Georgia home to about 12,000 British Columbians either born here or somehow washed ashore. A recent Facebook post on one of our community pages argued that, since about a third of the island’s population consists of people who arrived in the last five years, considerable effort should be made to preserve the community’s way of life – our local customs, festivals, and so on.

If you make that argument about a particular community in English Canada, some might agree and some might disagree – but very few will seriously question the premise that different areas have distinctive identities. But if you simply expand that argument to English Canada as a whole, you are accused of all sorts of “isms” and “phobias”. That’s political correctness at work – and it prevents a healthy and honest discussion of immigration in Canada.

All content on this website is copyrighted, and cannot be republished or reproduced without permission.

Share this article!