Whither Canada: Satellite or Independent Nation? (Full Speech)

Editor’s note: When Brian Graff realized there was no digital version of Walter Gordon’s Whither Canada speech, he used OCR to make it available for Canadians to read on Dominion Review! Here is the speech in full. Graff has highlighted key sentences and sections. You can find Graff’s analysis of the speech by clicking here.

Remarks to the National Seminar, National Federation of Canadian University Students, at the University of British Columbia, Monday, August 29, 1960

You have invited me to open the discussion on the broader aspects of “Research, Education and National Development,” a subject that is comprehensive in scope but at the same time a bit elusive in its outline. One may ask: Research of what kind, for what purpose, and for whom? Education of what kind, for what purpose, and for what proportion of our high school graduates? National Development of what kind, for what purpose, and for whose benefit? If we can answer these questions, if we can come to some measure of agreement about our broad objectives, then perhaps we may begin to come to grips with the subject for discussion. But without such agreement, without some definition about goals and objectives, I doubt if we should get very far. So, I shall begin my remarks with a somewhat dis-cursive review of some existing trends and some of the problems of the Canadian economy as I see them. Having done this, I shall indicate my own personal views about what the broad objectives of Canadian policy should be. And finally, I shall try to indicate my conception of the roles that research, education and national development should play, given the broad objectives of policy that I shall by to outline and define.

In the fall of 1956, nearly four years ago, the Royal Commission on Canada’s Economic Prospects submitted its Preliminary Report, Its Final Report was completed a year later. The Commission’s conclusions were predicated upon certain arbitrary assumptions or premises: that there would not be a nuclear war; that there would not be a serious depression like the one in the thirties, or prolonged periods of mass unemployment; and that our governments would pursue sensible, flexible policies designed to meet changing economic and political conditions at home and abroad.

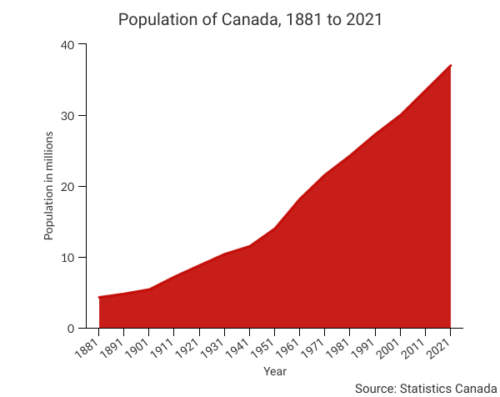

On the basis of these premises, the Commission put forward some tentative and very carefully qualified estimates of what economic conditions in Canada might be like twenty-five years hence, i.e., in the year 1980. These estimates were considered at the time to be rather optimistic. They indicated that twenty-five years from now Canada’s population might have increased to about 27 million; that the Gross National Product might be tripled; and that per capita net incomes should have increased quite substantially. In addition to these forecasts, the Commission noted a number of important economic trends and suggested that the structure of the Canadian economy might change over the twenty-five year period in various ways. I should like to remind you of some of these conclusions.

The rapid movement of people from the farms to the cities and towns that has occurred since 1939 may be expected to slow down, and in fact has already done so to a Considerable extent. But as a percentage of a much larger civilian labour force, the number of people engaged in agriculture in 1980 may be no more than 6% or 7% of the total compared with over 30% before the war. In twenty years’ time about 80% of the population may be living in urban centres. It is a simple fact that Canadians are no longer agricultural and rural in their way of life. We are now and will become increasingly, an urbanized industrialized society with very different problems, objectives, needs and values from those that preoccupied us as recently as even twenty years ago.

I might add in parentheses that I am impressed by the great inflow of people who have come from Europe since the end of the war to live in my hometown of Toronto. Most of these people are gay and intelligent as well as hardworking. They will make a real contribution to Canadian life in the years to come, and already they are beginning to wield considerable influence, as they should do. They are city people for the most part, and they will not be content for long with the traditional solemnity, particularly on Sundays, that Toronto was noted for in the past, or with the general drabness and lack of beauty in our public buildings and institutions that we have inherited from a different age. Those of us who were born in this country have a great deal to learn from these newcomers about living in big cities, about how to get the most enjoyment out of life, and in terms of entertainment, of friendship, of neighbourliness and close-knit family ties.

The fundamental change to which I have referred, the shift from the farms to the cities and the fact that people now have appreciably higher incomes and much more leisure time, has posed challenging problems for our municipalities, many of which have not yet been settled. These problems will not be resolved, I think, until there is a clearer definition of the respective responsibilities of the municipalities and the provinces for the costs of social services of all kinds, and also probably for the cost of education. The financial difficulties of the municipalities will have to be recognized one of these days by the two senior levels of government in this country, and something done about alleviating them.

The changed way of life in an urban industrial society has brought with it a need for the kinds of collective security measures against unemployment, against sickness and other calamities, and for old age that are now beyond the capabilities of the individual to handle by himself. This has meant a great deal more activity on the part of government at all levels than was necessary or desirable when the country was in a more primitive stage of its development. Many people are inclined to deplore this trend, without perhaps fully realizing the changed conditions that mainly are responsible for it. But I suggest to you that increased governmental activity in the areas I have mentioned is both necessary and inevitable in the new kind of society in which we now live in most parts of Canada. Certainly, I can see no prospect of a reversal of the present trend.

In its report, the Commission forecast a considerable expansion of our highly important natural resource industries and the refining and primary manufacturing activities based upon them. There are some things we can do to encourage development in this important sector of the economy – for example, we should not permit the exchange rate for the Canadian dollar to get too high, as this tends to raise the costs of our export products in terms of foreign currencies – but in the last analysis, the expansion of these industries will be dependent mainly upon the demand in other countries, primarily in the United States, for industrial raw materials. The rate of increase in this demand is not likely to be an even one, and as a result, we shall probably have to face periods when there is surplus capacity in this sector. There is surplus capacity now, and there are those who think this condition may prevail for some time to come. But over a span of years, the resource and primary manufacturing industries can be expected to expand, and should continue to provide employment for about 10% to 12% of the labour force.

It is not always appreciated that, if Canada is to be prosperous and if we are to have a high level of employment, it is important also that our secondary industries flourish and expand their operations. In 1955, these industries accounted for 22% of the total output of the country (compared with 17% in the case of the resource and primary manufacturing industries and 13% for agriculture). They provided employment for 20% of the labour force (compared with 11 1/2% for the resource and primary manufacturing industries and 15% for agriculture). According to the Commission’s forecasts, it is to be hoped that these secondary industries will continue to provide employment for about one-fifth of the labour force, and that by 1980 they will account for about one-quarter of the total output of the economy.

I am emphasizing these facts because many of our secondary industries are in trouble these days. And there are a few people who do not seem to worry about this very much. In fact, one hears it suggested sometimes that Canada should concentrate her main attention on our great resource industries, which for the most part are relatively efficient, and let our secondary industries more or less go by the boards. This is a dangerous concept. It is not a case of the resource industries or the secondary manufacturers. We need them both. And we cannot hope to have high levels of employment in Canada unless all the major sections of our economy, including secondary industry, are doing well. We should, of course, continue to emphasize the great importance of our resource industries and do everything possible to ensure that their costs of production remain competitive in world markets. But as I have said, the rate of activity in the resource industries, even if their costs remain competitive, will depend to a very considerable extent upon conditions beyond our own control, i.e., upon the demand in other countries, principally in the United States, for our exports of industrial raw materials.

The rate of expansion of the secondary manufacturing industries, on the other hand, will depend upon the growth of the domestic market and the share of it that these industries can secure. This, in turn, will depend in the long run upon the relative efficiency of these secondary industries and upon their ability to keep their costs of production down and competitive with imports. I for one am very much against high rates of tariff protection. And I see no reason why such rates should be excessive if steps are taken to maintain the exchange rate for the Canadian dollar at realistic levels, if money is relatively cheap and reasonably available, and if our tax and fiscal policies are designed to encourage growth. But whether we like it or not, some moderate protection will be needed if Canadian secondary industry is to prosper and to provide employment for a substantial proportion of the total working force. This is one of the facts of Canadian economic life that there is just no escaping.

Another trend that was referred to by the Commission was the pattern and the volume of our foreign trade. It seems probable that a high proportion of our exports and of our imports will continue to flow to and from the United States, and that, for the most part, our exports will consist of industrial raw materials. Canadians would prefer it if the pattern of our foreign trade – both exports and imports – was more widely diversified. And if the United States would change its tariff policy so that we would have a better chance to process our raw materials in Canada and export the finished products. But as of this moment, the prospects of these events happening do not seem very great.

We hear a lot these days about the potential effects on Canadian exports of the European Common Market, and sometimes, that we should explore the possibilities of establishing a Common Market or a free trade area on the North American continent. In my opinion, we should rejoice if, as a result of the Common Market, the countries of Western Europe become more prosperous. For one thing, this should provide an obstacle to the spread of Communism. And in the long run, this increased prosperity may result in increased exports to that area from Canada of such things as newsprint and some of the base metals.

But we should think twice before concluding that the same approach would be desirable on this continent. After all, some of the keenest promoters of the common market idea in Europe have political union as their ultimate objective, a union – incidentally – in which not one of the present countries would wield a dominating influence. A similar approach on this continent might have a very different result if eventually it led to some kind of political union between Canada and the United States. In our case, because of our much smaller size, this would really mean absorption by the United States. This is a prospect which I, for one, would not rook upon with relish – not that I am in any way anti-American but just because I think Canada has something to contribute to this weary, troubled world as a separate, independent nation with no axe to grind at the expense of any other country anywhere.

In this connection, the Commission had quite a lot to say about the extent to which Canadian industry is owned and controlled by non-residents, mostly by citizens or corporations in the United States. Foreign investment has been helpful in the rapid development of our country, and we have gained a great deal through the connections that many of our larger companies have with their parent companies in the United States and elsewhere. These benefits include access to management know-how, technological developments and research, and, in the case of many of our primary industries, to assured markets for their products. But, looking at the picture as a whole, I think we have allowed this trend to go too far. There is no other country in the world, to my knowledge — certainly no country that is as fully ” developed economically as Canada — which has so much of its industry controlled by non-residents. We shall have to reverse the present trend if we really wish to maintain our identity as a separate nation on the North American continent.

This may be an appropriate place to remark that the attitudes of Canadians about our economy differ somewhat from those of our American friends about the economy of the United States. In that country, there is greater and more vocal insistence upon the advantages of “free enterprise” and upon the subsidiary role that government should play. In Canada which is sometimes referred to as an economic anachronism – governments have always played an important and some-times a dominant role in economic affairs. This has been the case from the beginning, as even a cursory reading of the history of the CPR will show. We have come to accept the concept of public ownership in Canada in certain fields: the CNR the TCA, the Hydro Commissions of Ontario and Quebec, the CBC, the National Film Board, the PGE, the Canadian Wheat Board, are a few examples of what I mean. The cooperative movement is steadily gaining ground. While there is no element of public ownership here, nevertheless the co-operative method of doing business is not exactly what people have in mind when they talk about the advantages of “private enterprise” or free enterprise” with their connotations of untrammelled competition and a free market economy.

In the so-called private sector, many of our largest companies which wield a dominating influence in their respective industries are controlled and directed, not by individual Canadians but by people who reside outside our borders. To this extent, Canadians do not make the day-to-day decisions in the economic sphere. Again, this is hardly what we mean when we talk about “free enterprise.” Certainly, it is not “free enterprise” in any national sense insofar as Canadians are concerned.

There are, of course, large sections of Canadian economic life that still are relatively free. Small businessmen, professional men and farmers can still be independent up to a point, and speaking as one of them, I hope this will long continue. But taking the economy of the country as a whole, I suggest the term “mixed enter-prise” rather than “free enterprise” would be a better way of describing it. Like the majority of Canadians, I dislike too much government interference, too much bureaucracy, too much red tape. And too much government control will always be particularly obnoxious in a Federal State like ours with its great differences in points of view and in the nature of the economies of the different provinces. But I am afraid that, in the age in which we live, governments – provincial as well as federal – must be prepared to take the initiative and to give a lead upon occasion if Canada is to remain free and independent and if we are to have a high level of employment throughout the country.

This brings us to a basic question about which we should make up our minds before we can discuss intelligently the most appropriate policies for Canadians to pursue. And that is, the importance that we attach to retaining our economic and political independence – or as much independence as is possible for any single nation in this shrinking world of powerful super-states.

There are tremendous pressures upon us to integrate the Canadian economy more and more with that of the United States. Hardly a day goes by, it seems, that some Canadian company is not purchased by a large U.S. corporation or by its subsidiary in Canada. Hardly a day goes by without someone making a speech or writing an article suggesting a “continental approach” to one or other of our eco-nomic problems; or asking if it is possible or if it really makes sense for a small country like Canada to struggle to remain free and separate from an enormous neighbour with ten times her population and fifteen times the value of her annual output.

The fact is that in recent years, whether we like to admit it or not, Canada has been losing steadily a considerable measure of her independence, both economically and politically. If we are sensible, we should decide either to accelerate the pace of further integration with the United States, politically as well as economically, or alternatively, take steps without delay to reverse the present trend. Either course, in my opinion, would entail difficulties and some unpleasantness. Free trade with the United States on any appreciable scale – even if the Americans were willing to consider this – would bring about a great disruption of Canadian industry and serious unemployment, certainly during an extended period of readjustment and probably for longer. And if this was not accompanied by moves in the direction of some sort of political union or affiliation, we might find ourselves in a very difficult position if, at some later date, some new Administration in the United States decided to abrogate the arrangement.

On the other hand, we could not hope to reverse the present trend and to regain some of our lost independence without paying some sort of price in terms of a less rapid rise in our standard of living, though not, I think of greater unemployment. (This is a price, incidentally, that Canadians have always been prepared to pay, ever since Canada became a nation, when the situation was explained to them.) Furthermore, we could not hope to accomplish our objective quickly. To be successful, we would have to work at it for many years and with great determination.

While a case can be made for either of the courses I have mentioned – faster integration with the United States or the regaining of our independence – I submit that there is no excuse whatever for failing to face up to the dilemma in which we find ourselves today. To do nothing, to refuse to recognize the situation that confronts us or to admit its implications, will lead inevitably to our becoming a more or less helpless satellite of the United States. (The great majority of Canadians might never fully realize just when or how this happened.) Like many other people, I have thought a great deal about this issue. Having done so, I for one am prepared to say without any qualification that I hope Canadians will choose to regain a greater measure of economic independence than we now have. I believe we could be successful in this endeavour over the next decade or so if we really put our minds to it.

When it comes to foreign policy and defence, however, I cannot subscribe to the thesis of James Minifie that Canada should go neutral. Is it conceivable that we could remain neutral if a war took place between Russia and the United States? I think not. In the first place, there is the matter of geography, and it seems unlikely that the antagonists would oblige by going around or even over us, any more than Germany did in the case of Belgium in 1914 and 1939. But, quite apart from this, the Americans are our friends – our very best friends – even if at times we may find their attentions a little overpowering. And the Russian Communists are not our friends, let us remember. We do not like their system, and we want no part of it. So, to me, it is idle to think we could remain neutral even if we wanted to if war should break out – and it would be nuclear war – between these two great powers.

This does not mean, to my mind, that we should become subservient to the United States or to anyone, for that matter. The United Nations and the NATO alliance are the cornerstones of Canadian foreign policy and should remain so. But, speaking personally, I feel less certain about NORAD and about the use of nuclear weapons that are not under Canadian control. Despite all the words – many of them contradictory that have been uttered about the NORAD arrangement that was entered into so hurriedly and obviously without much serious consideration in the summer of 1957, it seems to boil down to the fact that Canada has contributed a few squadrons to the American Air Force. Much publicity has been given to the fact that a Canadian airman is Deputy Commander of the NORAD Force, and that both the President of the United States and some unspecified official of the Canadian Government (possibly the Prime Minister) must give joint approval before any shots are fired in anger. I find these explanations unconvincing. To me, it seems farcical to suggest that, in a grave emergency, retaliatory measures would be delayed while the officials in question were located, the situation explained to them, and their approval given to repel attack.

Similarly, if Canadian defence forces are to be equipped with nuclear arms, including nuclear warheads for the Bomarc missile, I think a decision to use such arms and warheads should be made by the Canadian authorities and by them alone. I do not think this should be contingent upon the approval of the American authorities, or jointly by the Americans and the Canadian Prime Minister. If these are the conditions, I would prefer to see us get along, at least for the time being, without weapons that are not within our own control.

To refer back to the Commission and its forecasts, I am still optimistic about what Canada can accomplish over the long term if we manage our affairs intelligently. What we need, I think, is to agree upon the objectives that Canadians should aim for, and then to develop the policies that we should follow in an effort to achieve them. In thinking about a consistent set of policies, there are of course many different tests or yardsticks against which proposals can be measured. For example,

(1) Will they result in more jobs and less unemployment?

(2) Will they cause inflation?

(3) Will they make a real and substantial contribution to the defence of the Free World or of North America?

(4) Will they result in a further loss of Canadian independence, or the reverse?

(5) Will they benefit the people of Canada as a whole, or just particular groups or classes or sections of the country?

(6) How will they affect personal incomes and the cost of living?

(7) Will they tend to create difficulties for us at some future time?

(8) Will they benefit people in depressed sections of Canada, or people in other countries who are less well off than we are?

All these tests, and many others that could be added, are important. And all of them should be considered carefully before particular policies are decided upon. It will be quite apparent, of course, that some of the tests that I have mentioned are not mutually exclusive. For instance, a broad program of public works may help to relieve unemployment, but in some way it must be paid for and this may reduce personal incomes or increase the cost of living or cause inflationary pressures, either now or in the future.

Or, to take another example, excessive borrowing in the United States by municipalities when the Canadian dollar is at a premium may solve an immediate problem. But such borrowings may have to be paid off in the future at a time when our dollar is at a discount. In such event, the additional costs involved will have to be paid by somebody. In other words, we are not likely to arrive at policies that will meet all tests successfully or that will please everyone.

But in deciding upon the best course for Canada to follow in the years immediately ahead, it seems to me there are two factors above all others that will be of paramount importance. In the first place, the threat of serious and possibly chronic unemployment is beginning to frighten and to haunt us. I am not exaggerating. The fact is that when 4.7% of the civilian working force are unemployed and seeking work in July – in the middle of the summer – we can be reasonably certain that the number of people who will be without jobs next winter will be very high indeed. This problem will not be solved by rhetoric and exhortations, or by ad hoc measures of relief. It needs to be thought through, first of all, and then we shall have to adopt policies that are designed to correct the situation over the long term – even if they may offend some of our most deeply held and long-established myths and prejudices.

In the second place, as I have suggested, if we really do wish Canada to retain her separate identity as an independent nation, we will have to re-examine our pre-sent defence and foreign policies and do something about stopping and then reversing the trend under which such a staggering number of our most dynamic industries have fallen into foreign hands.

It follows from what I have been saying that, in considering the pros and cons of any policy proposals, there are two tests above all others that should be kept very much in mind, viz.,

Will the proposed policy result in more jobs and less unemployment?

Will the proposed policy result in a further loss of Canadian independence, or the reverse?

Now, where does all this lead us from the standpoint of research, education and national development? Well, I think the discussion so far should help to place these highly important questions in perspective. If we decide we want to recapture some of our disappearing independence and if we succeed in this attempt, all kinds of research work will be required in Canada. If, however, we are content to let the pre-sent trend continue under which more and more of our industry is coming under the control of non-residents, then I expect that a large proportion of industrial research will continue to be done elsewhere. There would still be need for fundamental research of various kinds in our universities and research institutes. But if it becomes apparent that Canada is going to come under the domination of the United States – either because Canadians don’t care or don’t know how to stop the present trend – an increasing number of our better scientists and research people in all fields may understandably decide to find places for themselves in other countries.

In the same vein, if Canadians are determined to remain as free and as independent as possible, we shall have an urgent incentive to improve our educational facilities at all levels and to make it both possible and desirable for a larger percentage of our high school graduates to go on to university. In particular, we shall have to take much greater care to see that no really bright boy or girl is dissuaded from continuing his or her education after high school because of financial considerations or because he or she has not been inspired or informed about the advantages of higher education.

It would be my hope that, in the future, an increasing number of Canadians will be encouraged to seek and to accept positions of responsibility in all parts and sections of our increasingly complex society. In addition, it will be important that more Canadians – and particularly more Canadians who have had a good education or who have risen to prominence in business, in organized labour, in farming, or in other pursuits – should be willing to express their views about public affairs and should not be afraid to identify themselves with the political party of their choice. Government at all three levels is becoming increasingly difficult and complex. The decisions taken by our government leaders affect all of us. We cannot expect these decisions to be necessarily wise or enlightened if our most talented but sometimes most fastidious citizens shun politics as something that is beneath their dignity.

As to national development, I would like to see this country twenty years from now with a population of 27 or 28 million people; with a considerably higher standard of living; with plenty of opportunities available for all who seek to work in a mixed enterprise economy as at present; with a considerable measure of decentralization of day-to-day economic decision-making in the private sector, but with a great deal more of our basic industries in Canadian hands; with a more rounded and complete program of social security benefits; with the responsibilities and the functions and the revenue sources of the provinces and municipalities better defined and more adequate for their needs; with greater cultural and recreational facilities for an urban people who have more free time in which to enjoy a rich and abundant life; and with a better educated people, taking a greater interest in public and community affairs.

I would hope that twenty years from now there may be less emphasis than there is today on material values. I am in favour of competition and I believe in the profit motive – but it should not be the only motive if our objective is a well-balanced, rounded, happy, and at the same time interesting and stimulating life for a people who can be proud of their accomplishments, their independence, and of their influence in the world for good. These are some of the things that seem to me important when we talk about Canadian development.

In conclusion, let me say that I make no apologies for this interpretation of Canadianism, or if you like, Canadian Nationalism. I have no anti-British or anti-French or anti-American or anti-European feelings. On the contrary, these people in particular are our very best friends, both in terms of their countries who are our allies and as individuals. But just as a Britisher or a Frenchman or an American is proud of his country, so I am of ours. I want to see Canada remain as free and independent as it is possible for any single country to be in this interdependent world. I want to see all Canadians share in a more prosperous, abundant, and satisfying way of life. But I hope we will not concentrate all our energies and our whole attention upon that intangible abstraction the economists call the Gross National Product. I would like to see us do more to help our fellow-citizens who are less well off than we are or who live in those sections of our country that are relatively depressed. I would like to see us do more to help people in less fortunate countries than our own. And finally, I want to see Canada take her place in the community of nations as one of the most influential and respected of all the so-called middle powers.

All content on this website is copyrighted, and cannot be republished or reproduced without permission.

Share this article!

The truth does not fear investigation.

You can help support Dominion Review!

Dominion Review is entirely funded by readers. I am proud to publish hard-hitting columns and in-depth journalism with no paywall, no government grants, and no deference to political correctness and prevailing orthodoxies. If you appreciate this publication and want to help it grow and provide novel and dissenting perspectives to more Canadians, consider subscribing on Patreon for $5/month.

- Riley Donovan, editor