Recently (late June 2024), Statistics Canada released the projections for Canada’s population for the next 49 years, all the way to 2073. There were headlines in The Toronto Star and other newspapers on these projections, and in particular on the revelation that Canada’s population in 2073 is likely to be approximately 63 million people – an increase of roughly 22 million.

While the Century Initiative, the corporate and bank funded lobby group that has been pushing for higher immigration, wants Canada to have 100 million people in 2100, the 63 million number would likely mean that the country would fall well short of this.

I wondered if, as the saying goes, “the devil is in the details” – and decided to delve into the projections myself. I was interested to see how StatCan came up with their projection, what biases there might be in their assumptions, and how using different assumptions might lead to different results. I used Excel to examine their projections, and understand their final numbers.

StatCan based their numbers on July 1st of every year. The then estimated the various components of population growth over the next 12 months. Their numbers start in July 2023, assuming that Canada had 40,097,000 people at that time.

Essentially, their formula for projecting Canada’s population was:

- Add “births”

- Subtract “deaths”

- Add (permanent) “immigration”

- Subtract “net emigration”

- Add “net non-permanent residents” (students, temporary workers, and asylum seekers)

Simple. For provincial estimates, they also estimate “net interprovincial migration” – but that of course does not impact national population growth.

Next, StatCan ran 10 scenarios with different assumptions. There are six “medium” growth scenarios (labelled M1 to M6). All of them project just under 63 million people in 2023, so it is unclear which specific one the newspaper headlines refer to.

There is a “low growth” scenario, which would see Canada have 47 million people in 2073 – only about 6 million more than we have today. Then, there is the opposite – a “high growth” scenario which estimates Canada would have 87 million people in 2073. This would put us well on track to meet, and even beat, the 100 million Century Initiative target.

The final two Scenarios are the “slow aging” and “fast aging” projections, that have the Canadian population in 2072 estimated at 83.5 million and 49.5 million, respectively.

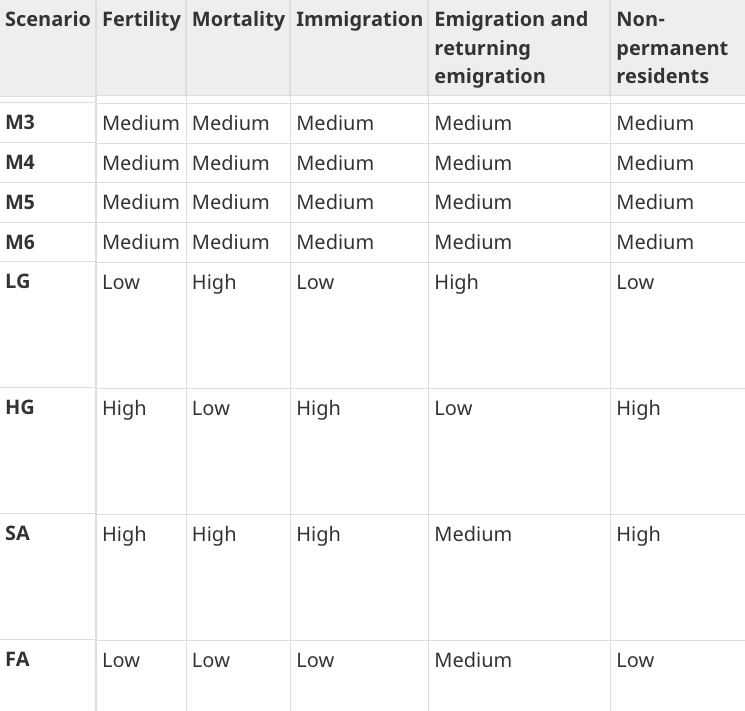

The easiest way to explain the differences is to show this table from the StatCan that simplifies the projections:

For simplicity, I only looked at three scenarios: Low Growth, Medium Growth M4, and High Growth.

The starting estimates for July 2024 differ slightly, at 40.8 million, 41.1 million, and 41.4 million. The main source of the differences is varying estimates of how many non-permanent immigrants came in in the year since July 2023: 327,000, 538,000, or 778,000.

The Liberal government has announced that it will reduce the number of temporary immigrants in Canada over the next three years, and the three scenarios I examined differ widely in the assumptions of how many people (net) will leave: 799,000, 640,000, and 431,000.

The government’s promise is around a 500,000 reduction in temporary residents, from 6.2% of the population down to 5.0% in three years. The assumption in the StatCan models is that non-permanent immigration will return to being fairly low – between a net outflow of 25,000 a year with the Low Growth numbers, or a net inflow of 90,000 with the High Growth numbers.

In the short term, there is not much of a difference between the three scenarios in terms of births and deaths, with around 370,000 births in the Medium M4 projections and around 335,000 deaths. In this scenario, the difference between births and deaths would entail a net population increase of around 25,000 in 2024/2025.

By 2072/2073, deaths exceed births by 246,000 in the Low Growth scenario, and there is roughly a 51,000 net decline in the Medium Growth scenario. The High Growth projections assume Canada would have a natural increase of 306,000 a year.

Net emigration is not a major factor. All three scenarios indicate that there is currently a net loss of a little over 30,000 of people a year, and it is projected to rise to between 52,000 and 60,000 in 2072/2073.

Other than how many non-permanent residents (NPRs) we let in each year (and ideally, they leave voluntarily or are deported if they don’t, so there is no net increase), and setting permanent immigration levels, Canada has little influence in the long term over any net population growth – which would have to be from births exceeding deaths. Governments can try to increase the birth rate, with better access to daycare or financial incentives, but these generally have not made a huge difference where tried, including in Quebec.

Net emigration is hard to predict. Canada has often had periods of large numbers of people emigrating, mainly to the US. This largely offset the high number of people we let in as immigrants, particularly from 1867 to the Great Depression. Canada also had a brain drain in the 1990s.

Naturally, I have been saving the most important factor in the growth projections to last, namely immigration. It is the factor over which Canadian governments have the most control (except for people overstaying their visas and remaining here illegally), but it is the most unclear what policy future governments will adopt. The Conservatives have been silent or coy on the issue, promising to tie immigration to housing or other factors, while meanwhile the Liberals are holding fast to the 500,000 permanent residents per year level for the next few years. This is just below the Century Initiative plan, which stipulates that Canada maintain a 1.25% immigration after reaching the 500,000 level.

All of the six Medium projections assume Canada has 500,000 immigrants a year to July 2027, then the number drops slightly. Around 2054, annual immigration is projected to exceed 500,000 again, and then to grow to around 579,000 in 2073.

Under the Low Growth projections, immigration would be around 450,000 this year, then drop to under 320,000 in the mid 2040s, then rise to just under 330,000 by 2072. Note that these levels are all far higher than immigration under Stephen Harper, when levels varied from 236,000 to 280,000 a year.

The High Growth scenario ignores the Liberals current cap of 500,000. It assumes that immigration will be 545,000 in the coming year, then hit 600,000 in 2028/2029, and continue to increase relatively constantly up to 1.03 million in 2072/2073.

It is sometimes more meaningful to talk of tge annual immigration rate as a percentage of the population. Immigration has been as low as 0.33% per year in 1985 (a post-WW2 low), and under Stephen Harper averaged around 0.75%. In 2021, immigration was over 1% for the first time since 1967. Canada’s immigration rate, prior to Justin Trudeau, had averaged under 0.75%. Under Pierre Trudeau, immigration averaged around 0.6%.

The StatCan projections in the short-term are for rates of 1.1%, 1.21%, and 1.34% for the Low Medium and High Growth projections for the next year.

The Low Growth Scenario declines to 0.7% in 2047, then is constant. Why this pattern? We’ll come back to that.

The Medium Growth version declines to 1.05% in 2047, then increases again to 1.23% in 2072.

With the High Growth projections, the immigration rate constantly increases to 1.56% in 2047, then keeps going, up to a whopping 2.19% in 2072/2073.

If you want to delve into these projections further, StatCan has a page that explains their assumptions and provides some additional graphs and information, which contains this description of their projections:

“The long-term targets (2048) were established based on the opinions of a group of experts on immigration estimates and projections from Statistics Canada’s Centre for Demography.”

This chart shows their assumptions:

After 2048, StatCan apparently kept the Low Growth scenario constant, then decided to increase the other scenarios. This despite the fact that the planet’s population will likely peak in the 2060s, and Canada might face stiff competition for immigrants against Europe, some Asian countries, and maybe the US as well.

No doubt the experts at StatCan have education and expertise I lack, and nearly all readers will also lack. That notwithstanding, there is a great deal of subjective choices in these projections. Civil servants are not likely to assume that policy will radically change in the near future, which is likely to happen only with a complete change of government, though a new leader for the existing government might make some tweaks. Civil servants are supposed to be apolitical.

Even so, there is some explanation about the larger forces at work in determining future immigration policy, as found in this section of the report:

“Among the factors that could influence future immigration levels, experts mentioned: the evolution of housing-related issues, pressure from certain influential groups in favour of strong demographic growth, the development of policies aimed at increasing productivity in the country, climate change, conflicts and natural disasters occurring elsewhere in the world, the capacity of infrastructures to respond to demographic growth, as well as public opinion, including the way in which the population reacts to a rapid transformation of society brought about by high immigration. Again, according to the experts, in the short to medium term, the retirement of the large baby-boom generation will continue to create pressure for high levels of immigration to meet labour shortage challenges. That said, in the longer term (e.g., from 2030 on), this pressure may fade once the exit of baby boomers from the labour market has slowed.”

Of course, AI and robotics could also mean a reduced demand for labour. Alongside the warning that in the future Canada and the US might face “jobs without workers” due to changing demographics, we also might face “workers without jobs” due to technological change.

Canada’s population has grown by around 11 million since 2000, to 41 million. It was never expected to grow this fast. StatCan issuing a projection of 63 million Canadians by 2073 is likely of little use to business or government, given it is nearly 50 years away. But chances are it is way too high.

The last 9 years under the Liberals have been an aberration when it comes to immigration, and particularly when it comes to non-permanent resident levels. In the short term, it is highly unlikely that the Liberals will be able to reduce the 2.5 million non-permanent residents by 500,000, particularly since they have backed off on the idea of giving many of them permanent residency as a quick fix. There have been no announcements of a crackdown or plan to increase deportations, and provincial governments have not been cooperative when it comes to jailing people awaiting deportation.

The media reported on StatCan’s recent population projection with little discussion of the potential range of population, depending on what political decisions we make and when. Canadians do, in fact, have a choice in these matters.

The last few years under Trudeau have been outliers, with persistently high immigration levels not seen since the early 1950s. It probably would have made sense for StatCan to run one scenario where immigration was reduced to 0.75% or less, either starting after the next election or lagged by a year or two. This would show what might happen if Canadians made that choice. This situation is probably more realistic than the High Growth projection, which assumes increases in immigration even before the next election, when the government has ruled that out.

My view is that Canada will grow to less than 63 million people. At least, immigration will need to be cut even more than the Liberal government’s planned reduction in temporary residents, which will be hard to meet. Without cuts to permanent immigration, housing supply is unable to keep up with demand, and the housing market will likely be in turmoil for a few more years. If Poilievre is elected and implements a policy to tie immigration to housing, he might have to make several rounds of immigration cuts before the market comes into some semblance of balance between supply and demand.

All content on this website is copyrighted, and cannot be republished or reproduced without permission.

Share this article!

Great article!