Blues legend Robert Johnson wrote and recorded the song “Crossroads” (Cross Road Blues) – the song he is most famous for and which many people likely know from the rock band Cream recording it in the 60s. There is also a legend around this song – that Johnson sold his soul to the devil at the crossroads in return for his musical genius.

The term “crossroads” is often used to describe a time when there is a crisis, or when a change of direction is sorely needed. If you go on the internet and search for “Canada at the crossroads” you will be shocked at how many times some version of this title comes up. It seems that Canada has almost always had some major problem or other requiring we need a new direction. Either Canada was never living up to its potential, or we were at the mercy of much larger forces battering us around.

So, when is Canada not “at a crossroads”?

Despite all our advantages, we must be choosing the wrong road often since we frequently lag behind the performance of other countries – particularly the US. Unlike our neighbour, Canada’s GDP per capita has been dropping for the last few quarters. Once again, we are at a crossroads – or worse.

I had forgotten about it until recently, but one of the most famous reports using the word “crossroads” was the 1991 report “Canada at the Crossroads: The Reality of a New Competitive Environment” by Michael E. Porter and The Monitor Company. Porter, who was associated with the Harvard Business School, was famous in the 1990s as one of the predominant experts and strategists on business competitiveness and management. His work is still relevant and often cited.

Canada had other major economic studies, including Walter Gordon’s report in 1957 (which was largely critical of Canada’s high levels of foreign ownership and control) and the 1985 MacDonald Commission Report (which essentially proposed the opposite of Gordon – a major free trade deal with the US). Those reports were both commissioned by the federal government, while Porter’s massive 1991 report was funded by the independent, business funded Business Council on Economic Issues – though with the co-operation of government officials and agencies.

Porter’s report was intended to look for Canada’s economic competitive advantages, and find a “New Economic Vision for Canada”. The Crossroads report is not easy to find – I could find no copies of it on the internet, and had to get one from the library.

A copy of the 468-page report was provided to then Finance Minister Michael Wilson. I frankly couldn’t bring myself to read all of this 33-year-old report – given how much has changed since then. I read the chapter summaries and numerous other parts to see what it found and recommended, and if it might still have some relevance today.

The report was published in October 1991, a most inopportune month. Mulroney announced his resignation 16 months later, and had already made major economic policy changes in the previous 7 years, including the Free Trade Agreement with the US, the GST, and major changes to immigration policy (which dramatically increased numbers, amongst other things). After the failure of the Meech Lake Accord, the government was ramping up towards the Charlottetown Accord in 1992, which itself ultimately failed.

Unemployment was in double digits from 1991 to 1994, so quick fixes were more likely than longer term strategic policy discussions. Interest rates were in the double digits, though inflation would drop in 1992 because of John Crow pushing interest rates to high levels. When the Liberals won the 1993 election, their major policy was deficit reduction and spending cuts.

It is hard to find much evidence to show that any governments followed the recommendations in the Crossroads report or that it had a lasting impact. In 2017, accounting firm Deloitte did its own discussion paper on the 25th anniversary that looked at the legacy of the original report and what the scenarios or strategies for the next 25 years might look like.

Even if governments ignored the 1991 report, other influential people in business or academia certainly found it to be useful reading.

There are a number of standard business school approaches that can be used to look at a company’s competitiveness, like the SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats). In Crossroads, Porter mainly uses his own tool, the “Diamond Analysis”.

The Diamond Analysis has been described as using 4 points:

- Firm strategy, structure, and rivalry

- Related supporting industries

- Demand conditions

- Factor conditions.

Here is a more detailed description of each:

Firm Strategy, Structure, and Rivalry

Firm strategy, structure, and rivalry define that competition leads to increased production and the development of technological innovations. The concentration of market power, degree of competition, and ability of rival firms to enter a nation’s market are influential.

Related Supporting Industries

Related supporting industries consider the upstream and downstream industries that facilitate innovation through exchanging ideas. These can spur innovation depending on the degree of transparency and knowledge transfer.

Demand Conditions

Demand conditions refer to the size and nature of the customer base for products, which also drives innovation and product improvement. Larger consumer markets will demand and stimulate a need to differentiate and innovate and increase market scale for businesses.

Factor Conditions

According to Porter, the most important of the five points is factor conditions. Factor conditions are those elements that Porter believes a country’s economy can create for itself, such as a large pool of skilled labor, technological innovation, infrastructure, and capital. One way for the government to accomplish that goal is to stimulate competition between domestic companies by establishing and enforcing anti-trust laws.

Frankly, I find Porter’s Diamond analysis tool to be inadequate for a nation state trying to figure out the best long-term policies it should embrace. I doubt that after WW2, countries like Japan, Germany, or South Korea would have been more successful than they were if they had used this model. The model gives little direction on issues like immigration policy or how much a country should spend on the social safety net. More importantly, the “Asian tigers” have been successful largely because they followed neo-mercantilist policies, while conversely, Europe’s success has been in developing the EU as a regional free trade zone and common economic rules and standards, which was then augmented by the creation of the Euro.

Even so, Porter’s thorough analysis in 468 pages provided a thorough and wide-ranging look at Canada’s economy and what sorts of changes might be needed to increase productivity and competitiveness. It is useful today, even if only as a critique of Canada’s longstanding weaknesses.

The last chapter of the book summarizes the findings and includes this diamond diagram that gives an indication of the problems Porter found and thought had to be addressed:

Of course, there is a lot more to be found in the summary that is more telling and useful than this simplification. Most of the recommendations expand on the above and are typical of the era – neoliberalism, and generally support for a smaller government confined to the role of providing education and support.

There is nothing really radical or controversial in this report – after all, it was commissioned by a group (Business Council on National Issues) that represents the interests of Canada’s biggest corporations – both foreign and domestically owned – to influence a conservative government. It accepts free trade and immigration as givens.

Porter wanted less direct government intervention in the economy, better coordination between governments, freer trade within Canada, improvements in education, more focus on innovation, and for Canada to focus on its strengths and comparative advantages. Porter also sees lack of domestic competition as a problem. Many of these things are still mentioned today when discussion turns to how Canada’s competitiveness can be improved.

He also has recommendations at the level of business firms or industries. Yet, I also found some things that are rarely mentioned or that hint at a different approach than we normally read in the business sections of Canadian newspapers.

My own views at the time, and today, were pretty much the opposite of the Mulroney agenda. I am an economic nationalist who believes that Canada needs to reduce foreign ownership and control, move away from dependence on natural resource and commodity exports, reduce political decentralization, rely less on immigration, and to create a government that is more active in investing in business or using crown corporations.

I believe that a country cannot be great without have great corporations that export, or do not limit themselves to the Canadian market alone. Japan, Korea, and Germany all have great corporations. Look at Britain, which used to have major manufacturers in automobiles, aerospace, and even small cottage industries (like Italy). It is hard to think of companies that are still both British owned and headquartered that sell goods to Canada, except perhaps Dyson and Rolls Royce (the jet engine maker – the car maker was sold to BMW years ago). Even Taiwan has the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), the computer chip manufacturer that has been in the news a lot in recent years.

One section where Porter is on the right track is when he talks about the importance of industrial clusters (page 66).

Canadian governments have had a tendency to spread things equally to each province instead of recognizing that clustering is important. This is an area where Paul Krugman’s theories won him a Nobel Prize. Porter uses Germany as an example of clustering, with an accompanying map. Hollywood and Detroit were obvious examples of clustering in the US – though both moviemaking and auto production are now more decentralized. Clusters mean domestic rivals competing against each other and being in close proximity to suppliers, a pool of experienced talent, and other inputs.

This is what Porter says on rivalry:

“As the framework has stressed, domestic rivalry plays an important role in innovation and in the development of competitive advantage in an economy. While openness to trade can partly substitute for the lack of competition at home, the evidence from a wide array of industries and nations confirms a strong association between active domestic rivalry and international competitive success.

Domestic rivalry, enlivened by proximity, pressures firms to innovate. The presence of local rivals nullifies factor advantages and promotes upgrading; it jars firms away from depending on the home market and pressures them to export. Import competition lacks these important benefits.

Domestic rivalry not only stimulates dynamism but, also unlike import competition, creates forces that work to improve the entire local diamond through encouraging specialized factor creation, the development of local suppliers and related industries, and so on.”

So, when Canadian companies are taken over, particularly in a merger or takeover with another Canadian company that will see one head office closed, Canada becomes less competitive and dynamic. Even if consumers do not lose out from less competition, the Canadian economy is worse off by having less rivalry.

There is one part of the Crossroads report that I did find to be extremely interesting and relevant today, but let me first skip over to another recent book “The Prosperity Paradox: How Innovation Can Lift Nations Out of Poverty” by Clayton M. Christensen and Efosa Ojomo.

This section is particularly useful in looking at the role of corporations in the global economy and in respect to how individual countries compete:

“We view economics as a nested system. The global economy contains national economies, which are composed of industries, which in turn contain corporations. Corporations are composed of business units, which are organized around teams, which define how employees coordinate their work. Employees, in turn, make and sell products and services to consumers, who have preferences that define what they will and will not do.

Scholars in the two traditional branches of economics—macro and micro—build models of how the global and national systems work on the one end, and at the other end how individuals prioritize and make decisions. However, most economic activity actually occurs somewhere between these two ends of the nested system: namely, in companies. Aside from welfare payments and people employed in government entities, companies essentially are the economy. Companies create and eliminate jobs, and pay wages and taxes. They implement government policy. They choose to invest or not invest. They respond to changes in interest rates. Companies build economies’ infrastructure, and in many ways companies are our infrastructure consumers, who have preferences that define what they will and will not do.”

From the same book, this following section is about how there are in effect two types of goods and services that generate jobs and economic activity:

“Local jobs are jobs that must be created in order to serve the local market…advertising, marketing, sales, and after-sale service typically fall into this category. They are often higher-paying jobs when compared with global jobs. Global jobs, while also important, are more easily moved to other countries to take advantage of lower wages. Manufacturing and sourcing of raw materials are perhaps the biggest culprits. With the advances in global supply chain management, global jobs are often at risk of moving across national boundaries to the next most “efficient”—or low-cost—labor market. By contrast, local jobs are essential to support market are not as easily transferable or outsourced to other countries. For example, jobs in design, creating innovations; they are less vulnerable to the allure of lower wages elsewhere.”

When the Free Trade Agreement went into effect after the 1988 election, part of the hope was that the branch plants in Canada owned by multinational corporations would switch from serving just Canada to having a global product mandate.

Our automobile manufacturing industry was covered by the Auto Pact since 1965, so it served North America with some limited exports to the rest of the world (some might remember the fiasco of GM selling 12,500 cars to Saddam Hussein in 1981, before the order fell apart). It was already integrated with the US market, but other plants would be affected. The result was that many branch plants closed in the early 90s, because it was often easier for US plants to increase production to serve Canada and close the plant here than it was to find new products to make using superfluous plants or capacity here.

Where Porter’s analysis shows insight is in a section called “Foreign Direct Investment and Canadian Competitiveness” (Pages 72-77).

He states:

“There has been a good deal of debate in Canada about whether foreign investment is good or bad. This, we believe, is the wrong question. In most circumstances, a nation is better off with foreign investment than without it. Foreign companies bring capital, skills and technology that normally boost productivity. The real issue is what foreign multinationals choose to do in Canada and how productivity in Canadian activities compares to alternative locations. The nature of their Canadian activities, in turn, influences the sustainability of foreign firms’ Canadian investments and their contribution to productivity growth.

The ten-nation study identifies three types of foreign investments: those that source basic factors, those oriented toward gaining market access, and those that establish or acquire home bases…”

While Porter is an advocate of free trade agreements and free flows of Foreign Direct Investment (“FDI”) and also was not going to recommend that Canada move away from the FTA and the looser rules on American FDI being able to come into Canada, he does note that where a corporation has its “home base” is extremely important. This might actual be the same country as where the actual owners and investors in that corporation themselves live or are based.

For example, many Canadians might recall the saga of the Avro Arrow interceptor jet airplane in the 1950s. Avro had also built the world’s second jet powered passenger airliner in the early 1950s, before Boeing and its 707. The cancellation of the federal government order for the Avro Arrow in 1959 by PM John Diefenbaker resulted in the company closing not long afterwards. It had no other viable products, and many of the talented people ended up moving to the US to work for NASA, other parts of the US space program, or other aerospace projects.

Avro was not Canadian owned – it was actually owned by British company Hawker Siddeley since 1945, when they bought up the assets of the government owned Victory Aircraft company that was set up to build bombers for WW2. But even though Avro was British owned, it was essentially an independent corporation that developed its own products and was not a mere branch plant operation run out of Britain. Avro did its own R&D, whereas the Canadian subsidiaries of the big US auto makers only did minimal R&D in Canada, such as cold weather testing.

Here is Porter on “Home Bases” (highlighting added):

“Assessing the contribution of foreign investment to productivity growth is based on the location of the home base activities for the product lines or businesses in which the foreign firms compete, the home base is where the essential competitive advantages of the enterprise in a particular product line or business are present. The firm usually locates less productive activities elsewhere, sourcing factors or seeking market access. The concept of the home base refers to individual product lines or business units. Indeed, a diversified firm may have a different home base for each of its business units.

The country of ownership determines where the profits from the enterprise ultimately flow, and thus is significant for national income. However, the country of ownership is secondary to the location of the home base for national economic upgrading. The location of a company’s owners does have a substantial influence on where its home base is located, but the two are not necessarily the same. It is possible for a product line, a business unit, or even an entire firm to have principal ownership in one nation and a home base in another.

Home bases gravitate to the location with the most favourable diamond for the product line or industry. Multinationals that locate home bases for some business segments outside their home country are becoming more common. Nestle, for example, is in the process of moving the headquarters of some of its business units outside of Switzerland when that country does not provide the most dynamic environment, such as in candy. Similarly, the home base of CBS Records remains in the U.S., where the most innovative climate in popular music resides, despite its purchase by Sony. Autonomous regional home bases may also be located outside the home country. GM’s European automotive operations have traditionally had their home base in Germany, for obvious reasons.

Compared to more limited foreign activities, the presence of home bases in a nation offers the widest set of benefits to the nation’s economy compared to more limited foreign activities. The home base is the place where the firm normally contributes the most to the local economy in a particular industry. The home base represents the locus of innovation and productivity growth. It is also the location where the most beneficial externalities to other industries in the economy occur, via the diamond. The firm invests in specialized factor creation, acts as a sophisticated buyer for other local firms, acts as a sophisticated related and supporting firm for other industries, and helps to create a vibrant local competitive milieu. Spillovers of knowledge and expertise are the greatest, and the local diamond most strengthened. The result is the best climate for upgrading and productivity growth. The best situation is if the nation is the location of both the home base and ownership, because here the profits flow to the nation as well. However, the profit stream may often be less significant than the other benefits.”

Where I disagree with Porter is over the role of natural resources in our economy. He states this:

“The Canadian economy is heavily based on natural resources, as is evident from the analysis in Chapter 2. Some argue that such industries are inherently less desirable than “high-tech” or manufacturing industries. This logic is flawed.

There is nothing inherently undesirable about resource-based industries, provided that they support high levels of productivity and productivity growth. As noted earlier, resource-based industries can make a nation wealthy where its resource position is highly favourable, and Canada has benefited tremendously from its abundance of natural resources.”

Unless a country can dominate the market for its main resource, like what South Africa did with diamonds or Saudi Arabia does with oil, there are potential problems, and Porter does cite some of these, include resource depletion. He notes:

“Competing solely on the basis of resource advantages in commodity industries makes nations particularly vulnerable to subsidies and to exogenous price and cost swings…

However, resource-based economies often develop a set of policies, institutions, attitudes and behaviour reflecting their resource abundance that make it difficult to move beyond the factor-driven stage…

Resource abundance has a tendency to make firms, workers and governments complacent. Firms begin to believe that they do not need to innovate in order to compete. Powerful resource companies influence government policies in ways that preserve their existing modes of behaviour… The result can be a system poorly equipped to deal with change…”

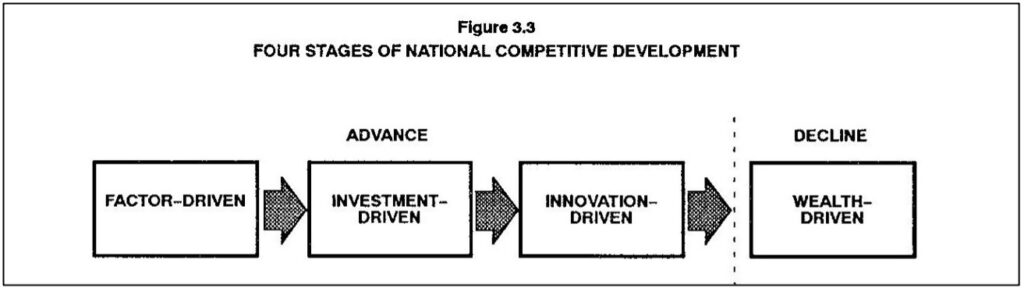

Porter mentions above the “factor driven stage” of development. Elsewhere he lays out the stages of economic development that nations might go through, as shown in this diagram:

Here is the text that explains this better (highlighting added):

“There are four stages of national competitive development: factor-driven, investment-driven, innovation-driven, and wealth-driven. All nations begin at the factor-driven stage. Here, virtually all the nation’s internationally successful industries draw their advantage almost solely from basic factors such as natural resources or low cost labour. In the investment-driven stage, a nation and its firms actively invest in factor upgrading and in modern, efficient plants and methods, normally based on foreign technology. Advantages in the diamond widen to include more skilled labour, better infrastructure and scale facilities. This allows the nation’s firms to compete in the standardized, price-sensitive segments of more sophisticated industries. Yet firms in this stage are not typically innovators or differentiators. In the innovation-driven stage, all four determinants are in place and work together to foster continuous innovation and upgrading in a wide range of industries in the economy. Here, an economy reaches the height of productivity. The fourth, or wealth-driven stage, is a stage of decline. In this stage, vitality ebbs and redistribution of wealth, rather than its creation, becomes the focus…

There is no inevitability about progression through these stages. Relatively few nations have moved beyond the factor-driven stage. The challenges required to establish pools of specialized factors, build sophisticated home demand, develop a range of home-based related and supporting industries, and put in place the dynamic rivalry necessary for advancing to the innovation-driven stage are daunting barriers for most nations. Active local competition is a prerequisite for advancement because it is what pressures upgrading. Those nations that have achieved substantial progress in the postwar period have all been characterized by active local competition — for example, Japan, Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong. The attempt to develop via monopolies, in contrast, is perhaps the most common error of developing countries.”

I would add that the fourth stage is also a stage of “rent” collection or financial engineering instead of actual innovation, as opposed to just being one mainly of socialists calling to tax the rich.

I suspect that, like many people who do consulting or are hired for their expertise, Porter’s message is tailored towards the interests or outlook of the client. Consultants rarely will bite the hand that feeds them, and will at least tone down the message to make it more palatable.

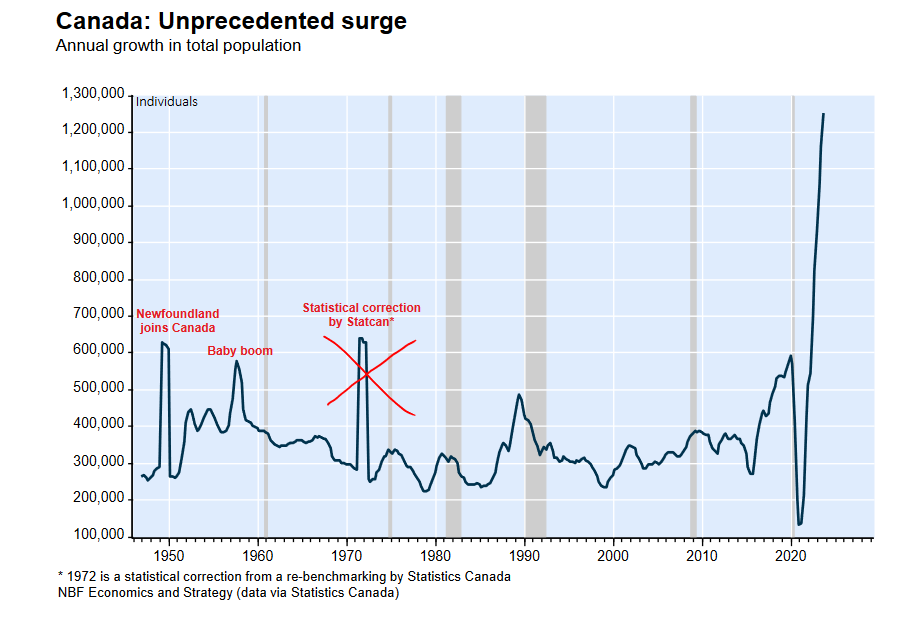

But countries as large as Canada or the US may actually be a mix of stages, and certainly Canada has provinces where natural resources dominate. Canada’s problem is that with a high immigration/population growth strategy since 1990, and particularly since 2015, resource extraction industries cannot expand, or face decreasing returns (lower quality sources, faster depletion). Even if the resource driven industries innovate, that means fewer jobs for the same output.

Canada is again at a crossroads, given our GDP per capita is falling while the US economy is outperforming every G7 country in nearly all respects. Until the early 1970s, Canada’s economy closely followed US trends in areas such as unemployment and inflation, but ironically this is sometimes less true since 1990 than before 1973. In the early 1970s, our GDP per capita gap with the US was decreasing while now it is increasing.

Canada has often had the opportunity to change and shift away from natural resources and branch plants, but when we come to a crossroads we seem to not turn down the roads taken by Japan and South Korea. By choice, by inertia, or because powerful interests resist change, we end up going down the same old road. Free trade with the US in 1988 might have seemed like a radical change but it was really just speeding up previous trends away from PM John A. MacDonald’s National Policy.

Porter understands that innovation is important in any industry or economy. The Trudeau government is spending billions of dollars to subsidize new plants in the auto sector with the shift from internal combustion engines (ICEs) to electric vehicles (EVs) or hybrids. These subsidies and deals have come under a lot of criticism, and we should question them given the cost and importance of the auto sector to Canada.

If we ignore the “diamond” model, but use some of Porter’s more general ideas, the real issue for Canada is if these battery plants and other investments are actually wise.

For example, one investment in EV battery manufacturing is with Volkswagen – but Volkswagen has no assembly plants in Canada or other major investments planned. Volkswagen makes cars in the US and Mexico, and most of the decisions are made in Germany, or even at the headquarters of its US subsidiary. Volkswagen apparently is not going to do much R&D in Canada. This is not the “home base” but just another branch plant – one that takes advantage of Canada’s excellent highly educated workforce and other “factors” needed for production (infrastructure, raw material, electricity, and so on).

The federal government also reportedly spent $34 billion on the TMX pipeline – which once finished will allow exports of oil, but not do anything further to increase productivity or drive innovation.

For Canada to prosper, it needs to move away from natural resources, and move away from branch plants towards corporations that have Canada as “home base” and are independent. We also need to have more competition and rivalry between corporations based here.

Free trade deals, including USMCA, limit Canada’s ability to reject foreign direct investment, because Canada has to treat potential foreign investors the same as domestic ones in most sectors. The way around this is for Canada to generally take a more aggressive stance on rejecting nearly all corporate takeovers or mergers, and to create more domestic competition and rivalry even when it is unclear if consumers will be hurt.

Every time a head office in Canada is closed or merged in with another head office, we lose not just jobs, but competition. Business organizations and their management teams and ability to function take decades to develop – the destruction of head offices and the benefits we have from having more of them is not factored in by our governments or by the Competition Bureau. Perhaps this needs to change.

Trade agreements such as the FTA, its successor NAFTA (and subsequent agreements) limit Canada’s ability to pursue some nationalistic policies such as limiting Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Despite rejecting economic nationalism, Porter’s ideas in the Crossroads report do seem to encourage Canada to protect head offices, enact tougher laws on competition, and be willing to reject mergers and/or takeovers.

All content on this website is copyrighted, and cannot be republished or reproduced without permission.

Share this article!

The truth does not fear investigation.

You can help support Dominion Review!

Dominion Review is entirely funded by readers. I am proud to publish hard-hitting columns and in-depth journalism with no paywall, no government grants, and no deference to political correctness and prevailing orthodoxies. If you appreciate this publication and want to help it grow and provide novel and dissenting perspectives to more Canadians, consider subscribing on Patreon for $5/month.

- Riley Donovan, editor