TINA!

When I write “TINA!”, likely the first thought to enter any reader’s mind will be Tina Turner. Mind you, the title above would skew things even more.

I don’t think I have ever heard anyone say they disliked Tina as a person, or her music, and she had some great hits. She had a long tumultuous life, but it was still sad when she died a year ago at age 83. One of a kind.

But actually, I am referring to the acronym “TINA”, which stands for “There Is No Alternative”.

The simple phrase has been around for centuries, but it is most associated with Margaret Thatcher – a book on Thatcher even uses it as a title.

I tend to be a contrarian, and like to understand and solve problems, so I hate being told there is no alternative. I often think that TINA is used to shut down debate because people with power want to push ahead without public debate.

These days in North America, a huge issue is housing affordability and supply. Only one solution is being put forth by most people in government, the media or business – densification. TINA.

There is only solution that seems to get discussed: changing restrictive zoning rules – essentially, deregulation.

The loudest voices for densification are the YIMBYs. YIMBYism took hold in California around 10 years ago – a movement that was propelled by young, usually male people, often with a technocratic background. It turned out that property developers were also behind YIMBY “astroturf” (fake grass roots) organizations.

California and the US is not Canada or Ontario, where I live. Overly restrictive zoning may well be a legitimate problem in the US, but in Canada, we have 40-year record housing starts and we did not have the same housing bubble that led to the 2008 US financial crisis.

Ontario also has the Ontario Land Tribunal (OLT), formerly the OMB and LPAT – which is unique in North America as essentially being an appeal body that second guesses local planning decisions with “de novo” hearings, and a record of siding with developers 96% of the time, according to one study.

Canadian governments have mostly hopped on the “densification” bandwagon, including in Ontario, BC and federally – TINA.

But, for example, Toronto (the 416) in 2022 had about 200,000 units rezoned and unbuilt, and 400,000 more units in applications, most of which will be approved – according to a report from the Planning Department. Toronto has 45% of the housing starts in the GTA, up from 25% in the 1990s. And Toronto has had a maximum of 16,000 starts in recent years, so 600,000 units is about 37 years’ worth of housing.

I frequently have to point out these numbers to people on X/Twitter who call for massive upzoning and the elimination of single-family homes. Usually all I get in return is silence – people hate to admit error and will often go on ignoring evidence if their beliefs have become too deeply rooted.

The other big difference between Canada and the US is immigration. Immigration is a huge political issue in the US, mostly because of the masses of people trying to get across their Southern border since the Mexican peso crisis of 1994. Canada actually has far higher immigration rates than the US, and at least 1 million people who overstayed temporary visas were not being counted until recently.

For example, at 1.4% growth, Canada grew faster than any G7 country in 2019, and twice as fast as the next highest country, the US, which grew by 0.7%. The disparity has widened since then.

Yet, only since late 2023 has concern about high population growth and immigration become an issue covered in the Canadian media. Even then, both the federal government and the media have only talked about changes to temporary non-permanent residents (NPRs), not the permanent residents (PRs) who come in under the regular immigration stream – which roughly doubled from 260,000 in 2015 to 500,000 in 2025.

Yet, the narrative remains unchanged – no alternative to densification gets mentioned by governments or by the vast majority of the people reporting on housing in Canadian media.

Housing is complex. Any analysis has to consider supply and demand. There is also ownership versus rental, and then the issue of private, public or non-profit ownership. And there is the question of where housing needs to be built or should be built.

There are four general options – densification and three alternatives – that need to be discussed but are never explored, except by a few contrarians. These are:

- Densification of existing areas (or lands adjacent)

- Accepting Sprawl (do we protect farmland?)

- Population growth (immigration and migration)

- Decentralization

Densification

Most years from 1947 to 1992, the City of Toronto paid to have aerial photos taken of the entire city, and these are available online.

It is fascinating to see in detail how the city changed over 4 decades; the roads and highways built and how suburbia crept out to the boundaries, and then beyond.

The areas Downtown near the railway tracks were filled with buildings and all sorts of materials in 1947, as before the car was common, industry was located where both rail access and workers were available. By around 1960, most of the industry had left and in its place were oceans of parking lots mostly used by the new suburbanites driving to work. Nearly all of those parking lots are now gone.

Central Toronto, unlike most North American cities, has been densifying since the late 1960s, and few parking lots or brownfield sites remain. But nearby Hamilton, which had steel mills and industry along its waterfront long past Toronto, still looks a lot like the Toronto of 1970 – though even Hamilton is changing, as GO Rail and high prices in Toronto is causing Hamilton’s core to redevelop at a fast pace.

Densification is inevitable as long as the population of major Canadian cities continue to grow, but advocates for ending exclusionary zoning, “missing middle” or other forms of upzoning rarely if ever actually look at how much land is already rezoned (or has applications), what rate of new development is possible, and how much rezoning is actually needed.

If everything is upzoned, then where development goes first will be dictated by developers and their interests, and which ones are best positioned to develop their properties first. The problem is, this might not be what is in the public interest – there might be limited schools, sewer and water capacity, and so on in these areas. Meanwhile, the government may be building infrastructure, particularly subway or LRT lines where it makes the most sense, but those lines might be under-utilized, while others are over-capacity, if development is not channeled to the areas along those lines.

Toronto’s Line 4, the Sheppard Subway, was built in the 1990s and opened in 2002. It was long seen as a white elephant because little development was started before it opened, or in the first 10 years afterwards, when development charges were supposed to help pay for it. Meanwhile, development elsewhere in the City, like along the Waterfront (even in Etobicoke) or “The Kings” happened at a brisk pace.

Upzoning everywhere leads to chaotic planning – stable 100-year-old neighbourhoods full of heritage buildings become destabilized and have over-crowded schools.

Toronto still reveres the name of Jane Jacobs, but she was actually one of the people most responsible for protecting the older neighbourhoods. YIMBY neoliberals blame the Boomers for a lack of housing, but the current zoning policies in Toronto were mostly formulated by the mid 1970s, when the first Boomers were buying or renting, not trying to protect housing in the old neighbourhoods of the city. This story is well told by John Sewell in his book “The Shape of the City”.

Rather than densifying older stable neighbourhoods, not designed for high density and where owners resist, Toronto has ample land around it, and inside the Greenbelt. Ontario Premier Doug Ford tried to remove land from the Greenbelt in 2023, but he was forced to retreat given the scandal over developers having inside knowledge which they used to profit. But is the Greenbelt itself part of the problem?

Is Sprawl all that bad?

If an alternative to densification is ever mentioned, it is usually portrayed as a choice between densifying existing urban areas or the evils of urban sprawl. Despite the fact that massive numbers of people in the US and Canada are very happy living in the suburbs and needing to use a car, the suburbs are demonized. This has been the case since the mass-produced housing of Levittown in the 1950s, and even the Pete Seeger song “Little Boxes” from 1963 (written by Malvina Reynolds, not Seeger) that spoke of little boxes on a hillside: “And they’re all made out of ticky-tacky, And they all look just the same.”

In Canada, stopping sprawl is often couched in terms of saving precious farmland – and certainly Canada has only a small percentage of Class A farmland – and most of it is in the south, near our biggest cities.

In Ontario, government concern over sprawl started around 2000, after a decade when few condos were built but the 905 area around Toronto had seen a lot of suburban growth. Mike Harris’s Conservative government passed protections for the Oak Ridges Moraine in 2001, and started to study sprawl in 2002, using the name “Smart Growth”.

The Dalton McGuinty Liberals came to power in 2003 and quickly implemented Smart Growth policies, which included creating the Greenbelt in 2005 by combining existing areas in Oak Ridges and the Niagara Escarpment – an area of about 2 million acres where development is strictly controlled.

There is another Greenbelt in Ontario, around Ottawa, established in 1956 and governed by the National Capital Commission, but the one around Toronto is now the one usually referred to.

Ontario’s 2005 Growth Plan for the Golden Horseshoe was amended, expanded and updated many times since 2005, but there was one problem – nobody expected that the federal Liberal government of Justin Trudeau would opt for far higher population growth than the previous federal governments (of both parties) since 2000. Regular permanent immigration is being doubled, and while net non-permanent immigration had been low, it too shot up – particularly in 2022.

However, the Growth Plan anticipated growth, so there was a lot of undeveloped land inside the Greenbelt that was eventually to be urbanized under provincial policy. A 2023 study by the nonprofit Environmental Defence group estimated that there was room for at least 2 million homes inside the Greenbelt (that might mean 5 million people using the average of 2.5 people per household) – more than enough to meet 2031 targets.

So, farmland is going to be lost eventually anyway – this is government policy. Large developers have already bought large amounts of farmland inside the greenbelt, as “inventory” or a “land bank” to see them through the coming decades, and with returns well above expected inflation. If the farmlands were built out at even higher densities than Environmental Defence thinks possible, then there may be enough land for well past 2051.

And there is one other problem with a Greenbelt: “leapfrogging”. Even with the Greenbelt, sprawl is occurring on the other side of it, in Kitchener/Waterloo/Cambridge, Guelph, Barrie, Peterborough, and so on.

The pandemic saw a rise in people opting to move from the 416 out to larger homes in the 905 or beyond, as remote work meant the daily commute was gone or reduced.

And there is a bigger question – is it really that important that we protect farmland? If people have a choice between a tiny condo in a dense neighbourhood in the 416 and a bigger home outside the Greenbelt, will consumer demand even be there for all the planned densification to be financially viable?

Immigration

Most YIMBYs and other “supply side” advocates for densification usually go out of their way to avoid even mentioning cutting population growth. Of course, about 95% of Canada’s population growth is immigration, which is a sacred cow to politicians and many in the media.

Until 1990 under Mulroney, Canada had a “tap on, tap off” immigration policy, where immigration was based on “absorptive capacity” and would be cut if unemployment or other factors meant lower immigration was the best policy – like in the Depression (but housing or other factors might also be included).

In 1991, the Economic Council of Canada wrote a report indicating that Canada’s “ideal” population would be around 100 million, nearly 4 times the 27 million population of Canada at the time. This would increase GDP/capita by all of 7%. But generally other studies on immigration indicated little or no long-term gain from higher population, even if they took into account the eventual retirement of the Baby Boomers.

There are various estimates of the future population of the planet, by the UN or other groups, but one thing is clear – the planet’s population will peak before 2100, and then decline. A study published in The Lancet predicted 9.7 billion peak in 2064, (just 40 years away) then a decline to 8.7 billion in 2100.

The federal government has no policy on how many people Canada should have in 40 years or beyond – nor do any of the political parties. Should, or can, Canada keeps increasing its population long after most or all of our peers go into population decline? China, South Korea, Japan, Italy are already shrinking. Africa will be the last continent to have overall growth.

The only group with a clear target is the corporate-funded charity Century Initiative, established in 2015, which has the same 100 million target as the 1991 government report – but they do not look past 2100.

Their policy has been to increase immigration to 500,000/year, then keep it at 1.25% after that. This is exactly the policy that the Liberal government has adopted for permanent immigrants.

This raises the question: Can we figure out how much density we need, yet alone where in Canada it is needed, without having any longer-term plans?

If we had a population of 100 million, what industries would people work in? What standard of living would we have? What would be our export, since so many of our current exports are based on natural resources with finite limits?

The Century Initiative website indicates that the Toronto area will go from 8.8 million in 2016 to 33.5 million in 2100, more than Canada’s entire population in 2000. Vancouver will go to from 3.3 million to 11.9 million. People will need not just a place to live, but jobs and probably a place to work too.

The Liberal government has increased immigration targets every year, but this incrementalism has meant they have been able to duck public debate on population growth. At the same time, they have made more ambitious promises about cutting GHG emissions – which obviously are affected by population growth.

And we have also seen that GDP/capita growth in Canada has been falling behind that of the US, and has actually been in decline since the peak before the pandemic. Our inability to increase capital investment to keep pace with population is seen to be a major concern.

So perhaps it is no wonder that the “densification” advocates avoid discussing immigration. The reality is that we cannot plan how much density we need, or what type of infrastructure is required, without some idea of a target or a cap when population growth will have to stop. Given global population trends, and since our “optimal” population is almost certainly less than 100 million, it might even be that we have passed that number already.

Decentralization

Urban planning is subject to a lot of fads and jargon. One of the latest fads is the “15-minute city” – which is the idea that everyone should live within a 15-minute walk (and bicycle ride) of places where they can buy groceries, do banking, and buy other typical goods and services.

Of course, many people are happy with a 15-minute drive to these things – particularly if they like the comfort of air conditioning in summer and heat in winter while in transit.

The idea of a 15-minute city in part derives from “food deserts” in many US cities, where neighbourhoods have seen retailers close. In these neighbourhoods, the only option for people without a car is an expensive local convenience store with high prices and no fresh fruits and vegetables.

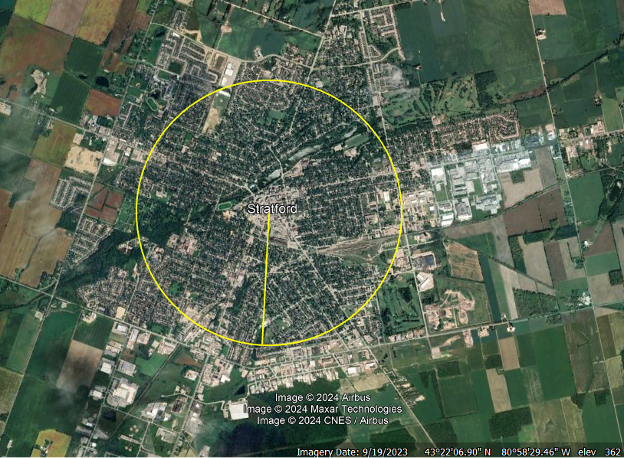

A person can walk around one mile in 15 minutes. So, anyone living in a small town or city with a diameter of 2 miles or less is living in a 15-minute city, in theory.

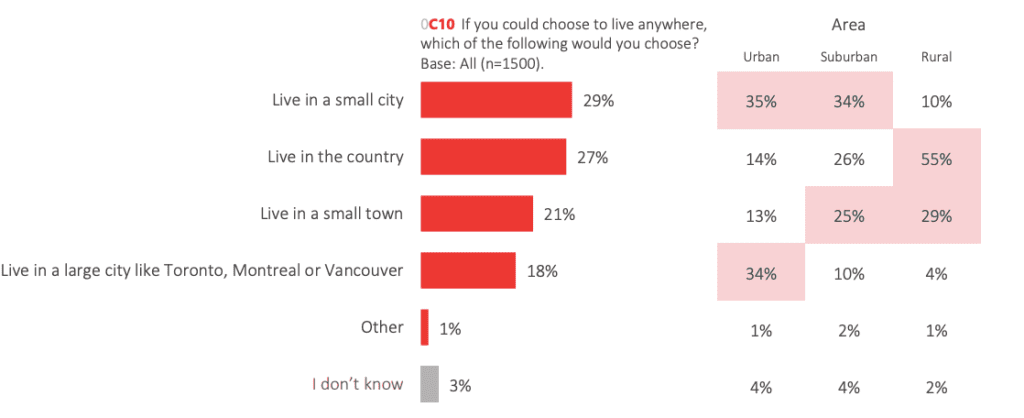

A recent poll by Leger commissioned by Canadians for a Sustainable Society showed that, if given a choice, only 18% of Canadians prefer to live in a big city – like the 3 major centres. On the other hand, 50% wanted to live in a small town or city, and 27% in the country.

And in fact, this is what has been happening since 2000, as cities like Halifax and Charlottetown have experienced high growth, and in Southern Ontario, cities outside of the Golden Horseshoe have experienced high growth. And of course, the population of Muskoka, Collingwood and other areas associated with recreation have also grown and had a shift towards more permanent residents.

As an example, take Stratford, Ontario, with a population of 31,000. Most of the City is within 1 mile of the Downtown (as shown on this map) and there are suburban shopping plazas on the edges which have grocery stores and banks. Cities like this are already 15-minute cities.

Trying to change suburban Mississauga or Markham into 15-minute cities is futile – and many people are happy and chose to live where a car is a necessity. Of course where older neighbourhoods can benefit from having more retail to prevent food deserts or banking deserts, adding these amenities is worthwhile. That might mainly be a US problem, however. This point was driven home by the closing of the Tops grocery store on Buffalo’s East Side – a largely Black community – after a mass shooting, and the resulting transformation of the area into a food desert.

Canada is filled with cities that still have a lot of room for redevelopment on brown field or vacant lands, like Windsor or Welland in Ontario. They likely have excess infrastructure, too. We have small cities that are in places surround by poor farmland – like Kingston or Sudbury in Ontario. Growth in other places might be harder – in Alberta and Saskatchewan, access to adequate water is likely more of a limit to population growth than any scarcity of farmland.

Even in Ontario, farmland away from urban areas is not very expensive. Estimates vary, but average farmland in Ontario costs under $30,000 an acre according to a CIBC estimate – and maybe as low as $17,000 – though $25,000 might be a good average based on South West Ontario.

Canada imports a lot of food – mostly from the US, but also Mexico, Europe, and South America. Ontario has greenhouses, but most food production is in the warmest months and is harvested in the fall. With global warming, the growing season in most parts of Canada will be increasing, and possibly with higher yields.

But if we densify existing cities, the costs are very high. Toronto did not have a major transit line after Line 4 opened, and Line 3 had to be closed early before the extension to Scarborough Town centre is complete.

Toronto’s Ontario Line has more than doubled in cost, to over $20 billion as of 2022 (and this is only from Eglinton Avenue south – plans include to run it at least up to Sheppard). That is about $1300 for every person in the province.

When the line is built, it will require subsidies to operate. And there are multiple other projects underway in Toronto (Eglinton, Finch, etc.) and in the 905.

It is time for a bit of math. How much land will $1 billion buy? Assuming $25,000/acre, this buys 40,000 acres, or about 62.5 square miles. The City of Toronto is 243 square miles in area (roughly 4 times 62.5) – so that is a little over $3.9 billion to buy farmland equal to the area of Toronto.

The full $20 billion would buy almost 800,000 acres of farmland, or about 35 miles by 35 miles!

We are spending huge amounts of money to save farmland – Ontario has 11.8 million acres, but to save all of it while also densifying from high immigration makes no economic sense. What might make sense is adding density in cities or towns which are small enough to not need expensive subways or rapid transit lines, with single family homes or other buildings under 6 storeys.

B.C. has about half as much farmland as Ontario, but we can also shift growth between provinces to some extent.

And now there are ways of growing food indoors at competitive prices – vertical farms can add density to industrial areas that are typically single-storey buildings now. Greenhouses can be built in areas where soils and/or climate make traditional farming impractical or uneconomic.

It makes absolutely no sense to add people to any Canadian cities that are so congested that subways have to be dug to accommodate more growth, when there might be ways to shift growth elsewhere, if not just reduce population growth altogether. Farmland is just not that valuable in dollar terms.

We tend to forget that Paris, London and New York have extensive subway systems, but they were mostly built by the private sector in an era before car ownership was commonplace, and fares covered the costs of building and operating them. Adding transit underground is expensive, and for reasons that are unclear, far costlier in North America than Europe.

In the US, the worst housing problems tend to be in states on the east and west coasts. This is from a 2022 Paul Krugman New York Times column:

“Soaring prices in the 2000s were generally limited to coastal metropolitan areas where zoning requirements and NIMBYism often made it hard to build more housing. Places like Dallas, where there are fewer restrictions, never saw as much of a price surge, probably because everyone understood that in the long run, prices would fall more or less to the cost of construction…

The bad news is that America’s housing affordability crisis has gotten even worse. Rents will probably come down over time in places where housing construction isn’t prevented by excessive regulation.”

Krugman cites Dallas, but Dallas is hardly known for tall condos and densified suburban buildings. What it does have is lots of land available for sprawl.

A 2023 article titled “Dallas tops cities with room to grow, boasting 90,000 acres of vacant land” states this:

“Dallas, Fort Worth, San Antonio and Houston all were ranked among the top five cities in the country with available land for additional construction…

“Across the 20 most populous cities in the U.S., there are 516,980 acres of land currently still awaiting development,” analysts found. Unsurprisingly for those familiar with the map of urban sprawl across the U.S., cities across the South and Southwest boast tens of thousands of acres of undeveloped lots each.

… “Texas remained the home of urban sprawl with the highest number of entries on our list,” according to the study by Yardi Systems’ Commercial Cafe.”

If neoliberal deregulation does lead to lower housing prices, the reason may be that the low level of regulation encourages sprawl and leads to a large supply of land already ready for redevelopment. This may be a more significant factor in lowering house prices than loosening zoning rules to allow multiplexes or higher densities within already built-up areas. Wy densify when vacant land is readily available and cheap?

And Toronto has a few wealthy families with large banks of land inside the Greenbelt. Why treat land as precious and hold it for development later if there is no limit to sprawl and you can replace the land you develop with more land a little farther out?

Canada has 40-year record housing starts, but some YIMBYs complain that since our population has nearly doubled since the early 1970s, we should be able to build far higher numbers of homes per year. But in terms of housing currently under construction, we are well above the 1970s, because high rise or multiple unit buildings are far more labour intensive, and take longer to build than simple wood frame, brick veneer housing on a vacant lot.

Montreal didn’t have the same levels of population growth as Toronto and Vancouver until recently (due to the economy, emigration to Ontario that in part resulted from separatism and language laws, and lower immigration levels) so there is more brownfield land and a greater ability to densify than in the Golden Horseshoe or B.C.’s Lower Mainland.

But when it comes to the centralization of population growth in Canada into a handful of cities, Canadians never look at how our patterns of population compare with other countries – other than a few YIMBYs comparing Toronto to Manhattan or Paris, rather than to Berlin or Chicago. In fact, Chicago is perhaps the urban area that is the closest to Toronto in terms of history, economics, culture and development. Both had major fires too!

But let’s take Germany and Scandinavia, and compare them to Canada.

Germany has 84 million people, double that of Canada. But Germany has only 4 cities with a population over 1 million: Berlin, Hamburg, Munich, and Cologne. Berlin has just 3.6 million people.

Scandinavia has just 27 million people, and 5 cities over 1 million: Stockholm, Copenhagen, Helsinki, Oslo, and Gothenburg. Stockholm is the largest, with 2.4 million people.

France has 67 million people, but only one city over 1 million, Paris. This city is 2.1 million on its own, but its region has 10 to 13 million people.

Canada has over 40 million people and 6 cities over 1 million: Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton and Ottawa. Montreal is the same size as Berlin at 3.6 million, and Vancouver is the same size as Stockholm. Toronto is 5.6 million, but this ignores Hamilton (0.7), Oshawa (0.3) and Niagara (0.24).

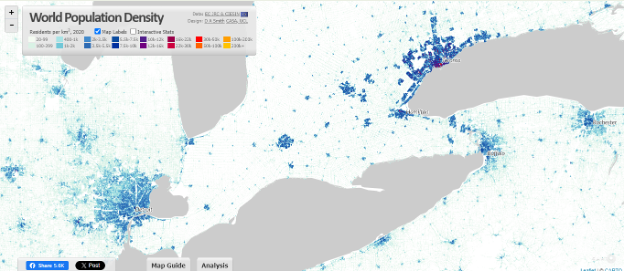

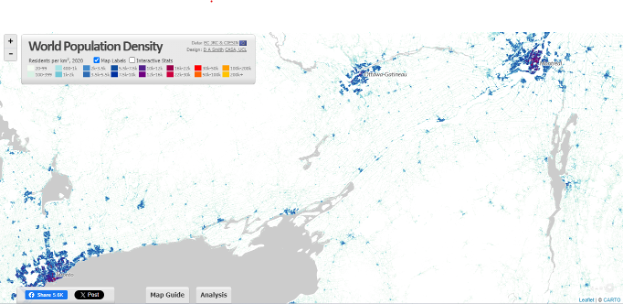

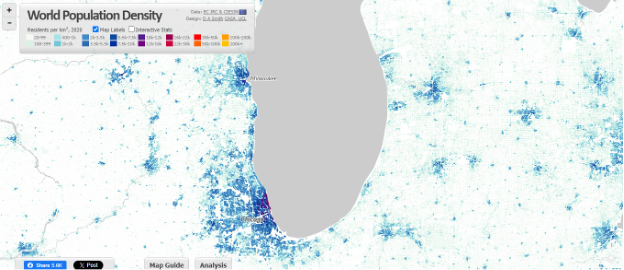

Canada’s population is 81.9% urban, and the countries mentioned above (and the U.S.) are slightly higher. There is an interesting website, LuminoCity3D, which shows population densities all over the world, and is worth using to look at Canada’s density distribution in more detail.

I looked at Ontario and parts of Quebec, since BC is mostly mountainous and is harder to compare without also showing what is essentially uninhabitable slopes. The maps below are at the same scale.

Map A, below, shows from Kingston on the right over to Michigan and upstate New York. Compared to Detroit and other cities like Buffalo, Toronto is far denser, with clearer urban boundaries, and far less density spreading out beyond that. The US is far more “exurban” than Canada, with housing developments springing up in the countryside on septic systems.

Notice how little density there is west of London and along Lake Huron – and this is purportedly one of the densest parts of the country, with the warmest climate (like in the grape growing Niagara wine region).

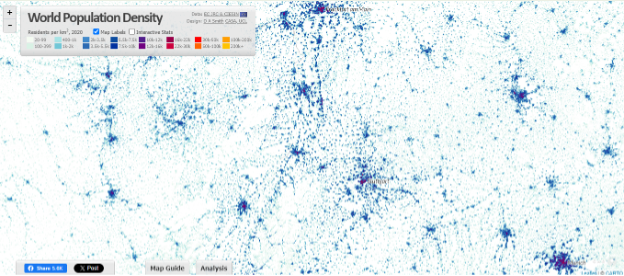

Map B below shows Ottawa and Montreal, and upstate New York including Lake Champlain. Algonquin park is where the Legend is shown.

Remember that there are plans for high-speed rail from Windsor to Quebec City, and Highway 401 (Autoroute 20 in Quebec) runs through here. This is Canada’s main transportation corridor for road, rail and the St. Lawrence Seaway, yet outside of the 3 major cities, density and the pattern of smaller cities is barely different from across the US border.

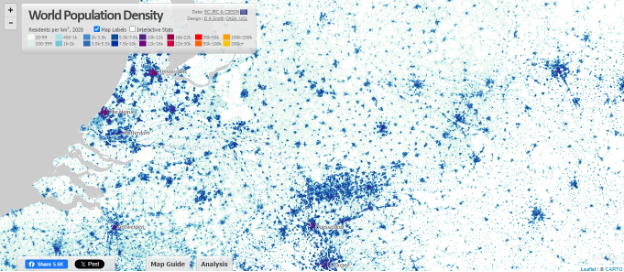

Let’s compare these with Europe and some US examples.

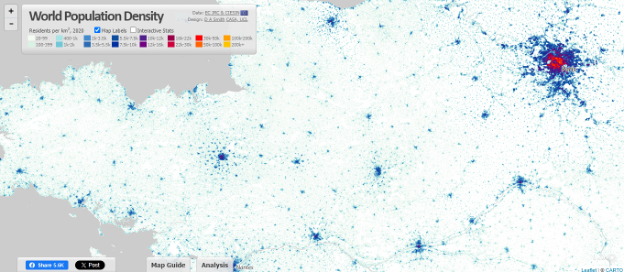

Map C is Germany – with Munich in the bottom right, Frankfurt and Main at the top centre, and Stuttgart in the middle – this is Germany’s industrial heartland (along with the Rhine) where BMW and Mercedes come from.

Map D is the Netherlands and Eastern Germany – Colognes is bottom centre, while Amsterdam, Rotterdam and Antwerp are along the coast. This part of Europe is densely populated but also has high agricultural production because rural land is used efficiently.

Map E below. Paris is obviously on the right, and the beaches of Normandy, where the D-day invasion took place, is to the north-west, in the middle of the top edge. The Loire River snakes across the lower half. This is France’s breadbasket for grains and cattle.

Map F below is the US Eastern Seaboard. From New York, through Philadelphia to Washington and Baltimore. Again, far denser than Ontario, and this is one of the few places in the US where rail service has levels of service like Europe.

Finally, Map G below is around Lake Michigan, including Milwaukee and Chicago areas, with Michigan (to the outskirts of Detroit on the right), Illinois and parts of Indiana and other states included.

This is a case of not seeing the forest for the trees.

Canada’s policy of high population growth is not justified. If the excuse that the current high levels are far below what is needed to deal with aging Boomers retiring, even those levels will not make a significant difference and they are best combined with raising the retirement age and helping people to work longer, if they are able and wish to.

Population growth has economic costs – bigger is not better and only 2 countries have both more people and higher GDP/capita than Canada. In an advanced economy, increasing capital available per worker is better than adding more workers – and the investments in housing do not make a country more competitive.

People who want to upzone land often do so with no idea of the current supply of zoned land or other factors needed to increase housing supply, nor is there any idea of how big our cities need to be – peak population, and when that is likely to occur.

Given that it takes years from upzoning to numbers of housing created sufficient to make a difference, cutting immigration, even if only for the short term, is the obvious first step. Canada’s immigration numbers are far higher than competing economies (save for Australia) and even a return to immigration pre-2015 levels would make a huge difference.

Canada is currently one of the richest countries on the planet and is second largest. We should not waste our best farmland, but it makes no sense to protect far more farmland that we might need, particularly if there is the potential to use land outside of urban areas more efficiently, like in Europe, or to direct growth to cities surrounded by farmland less worthy of protecting.

The planet’s population will likely peak below 10 billion – about 25% more than today. The problem of food supply is complex but is largely a product of income inequality, transportation/spoilage and other waste. Likely within 40 years, global population will drop. The major problem will be access to fresh water adequate for both human consumption and for agriculture.

Densifying cities may do little or nothing to protect endangered species or habitat, particularly if farmland is land banked and sensitive areas already identified for protection.

If we really want to save farmland, we would immediately reduce population growth by cutting immigration, as most immigrants significantly increase their environmental footprint when they immigrate to Canada. Emigration of their best educated people also hurts the countries immigrants leave to come here. Even spending a fraction of the costs we incur for infrastructure (and other things related to population growth) would be better spent helping other countries become greener.

There are alternatives to neoliberal YIMBYish densification. Some are obvious and are being ignored (cutting immigration). Others require a fresh analysis and planning of our future growth, and how and where we want that growth. This analysis should be based on the actual preferences of Canadians and not on false economies or only a limited view of what is best for the environment (which likely is not high-rise concrete condos as the only or preferred housing option).

With apologies to Tina Turner (again), maybe at some point we will say “We don’t need another high rise” as population growth in Canada stabilizes or starts to decline, along with the rest of the planet. When that happens, the cities will not change that much afterwards, much as most European cities change little. Will our cities compare with Europe’s if we deregulate zoning and let the market dictate urban form, regardless of what already existed around it?

Unlike the song title, we do need heroes, though. Neoliberals pushing for zoning deregulation are not heroes – and we should not deregulate or do the wrong things out of a panic to so something fast.

Apart from cutting immigration, the federal government needs to set up a Royal Commission or other study to look at the complex problem of future growth and prosperity. This should include: population (immigration levels, fertility, population distribution), urban planning, infrastructure needs, the environment, agriculture/food supply, and how we can maintain the high standard of living people expect, while meeting these other objectives.

Conclusion

Occasionally, I read online someone stating we should support even higher immigration, as they have the simplistic argument that we are a huge country with a small population/low density. They think, wrongly, that we could sustain far more people. Let’s call this the first or basic idea of growth, which goes back to Confederation but ignores the realities of expanding our population.

But there are wiser people who know that most of our land is poor for habitation, and we have little farmland, which is the first land we will likely use if we add a lot of people. This is the second idea of growth, that is more realistic about the limitations or barriers of where growth would actually occur.

The third response is to densify the existing areas and protect farmland – but that has lead to high housing costs and means few Canadians in future will be able to live in a ground related home (detached, semi, townhouse) – even though we are a huge country. This is the YIMBY position, and is the one that seems to dominate current discussion.

My response, as laid out in the article, constitutes a fourth and final set of ideas: the market value of farmland is actually cheap, and we don’t use what we have efficiently – does it make economic sense to spend a lot to save something the market values so low, other than where there is a clear environmental justification?

We import a lot of food, and the global population will peak within 40 years. Access to fresh water is actually more important than land in terms of limiting food production or where we farm.

Densifying cities is expensive – largely because of the costs of putting transit underground as density increases. But most Canadians actually prefer smaller cities and towns, and having a car. This is far better for having and raising kids than a condo.

In effect, if we reduce population growth, decentralize population more (like Europe), instead of centralizing people into a couple of huge cities/urban regions, it means people can have the detached home they expect, and we might generally be better off.

This fourth and final response takes into account the actual preferences of Canadians, and the economic costs of growth, instead of some utopian or ideologically driven idea of how Canada should develop in terms of population, urban planning, and housing.

There are concerns that the younger generations feel that they will have to accept less than their parents, or that they might never own a home, particularly one big enough to raise a family. This fourth and last response to the problems is the only one that deals with the complexities of the issues at hand. We live in a democracy – ultimately, if voters don’t like where we are headed then they will rebel in some way.

All content on this website is copyrighted, and cannot be republished or reproduced without permission.

Share this article!

The truth does not fear investigation.

You can help support Dominion Review!

Dominion Review is entirely funded by readers. I am proud to publish hard-hitting columns and in-depth journalism with no paywall, no government grants, and no deference to political correctness and prevailing orthodoxies. If you appreciate this publication and want to help it grow and provide novel and dissenting perspectives to more Canadians, consider subscribing on Patreon for $5/month.

- Riley Donovan, editor