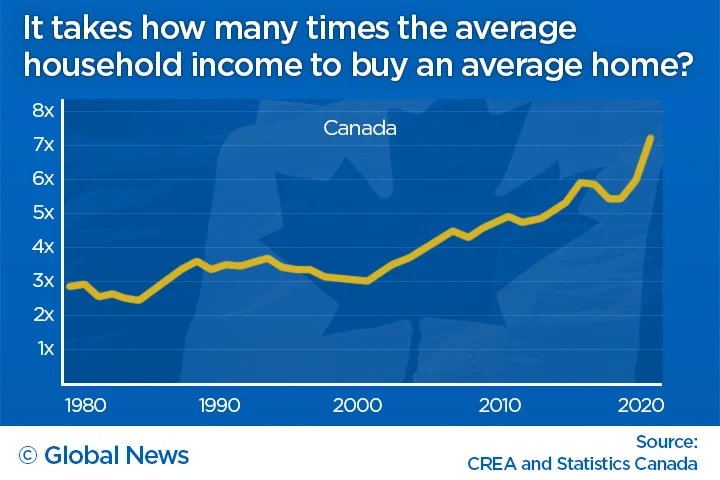

Housing affordability has been the major issue impacting average Canadians ever since the Covid pandemic has declined in importance.

For around two decades, if not longer, the housing policies of Ontario and BC have been oriented towards promoting the densification of cities and major urban areas. This became even more important with the introduction of greenbelts and other measures to protect farmland, aquifers, and natural areas that governments were under pressure to protect from sprawl.

Anyone who knows me knows that I will argue that the real problem behind both sprawl and housing unaffordability is high population growth from high immigration. The typical response from many politicians, experts, and the news media has been to portray this issue as a lack of supply. They make this argument despite the fact that Canada has had record levels of housing under construction within the last year, and despite our GDP being twice as dependent on housing construction as the US or any other G7 country.

YIMBYs (“Yes In My Backyard” housing activists) push for upzoning and various other changes to increase density in Toronto and Vancouver in particular, with the belief that adding to supply and densifying will lower prices.

But ignoring my stock answer that the problem is demand far exceeding supply because of high population growth, why is new housing so expensive despite densification policies that are supposed to increase affordability?

In the discipline of land economics, the Von Thunen model can be used to explain why prices are highest in city centres and lowest at the suburban fringe. This model can be used to help explain why, as a city grows bigger and gobbles up farmland, prices everywhere tend to go up. This process is similar to the way that making a pyramid bigger at the base, without changing the slope of its sides, means the peak gets higher and its average height also increases in proportion.

However, this argument is really a variation of my argument that growth is the culprit.

I came across something I had forgotten about that also helps to explain the problem of densification not leading to lower housing prices – Altus Canada’s 2024 Cost Guide, which describes itself as “Your guide to better understanding Canadian real estate development and infrastructure construction costs”.

Altus is a major player in Canadian real estate. It provides data and services to developers and other businesses and government organizations relating to real estate and construction. Their annual guide provides rough estimates on construction costs based on their extensive knowledge and involvement in real estate. We’ll come back to the guide later.

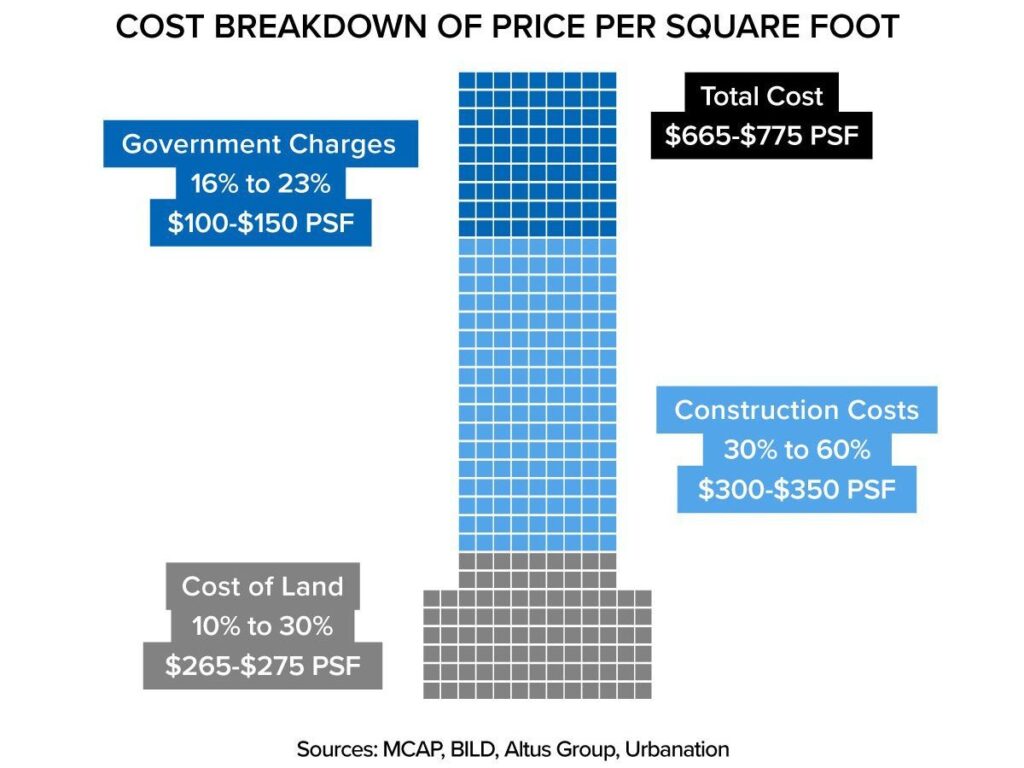

A graphic below that uses 2020 data from Altus provides a simple breakdown of cost elements for a typical condo building in Toronto with space selling for $900 per square foot. Land, at $275 per square foot, is about 30% of the final price. Government charges were 11% to 16%, and developer profits are in the range of 14% to 26% of the final price per square foot.

The remaining portion of the cost is construction, up to $350 per square foot, with a range of 33% to 39%. The 2024 Altus Construction Cost Guide provides a current breakdown, with specific numbers for different types of housing types and construction methods. It does this not just for Toronto but for eight other major cities across the country too. And it does this not just for housing, but for various types of commercial and public sector buildings as well.

Note that the graphic above combines hard and soft costs, with soft costs being things like the cost of architects & engineers, marketing, management, and financing. Soft costs often include permits and other government charges, but those were broken down separately. The 2024 Altus Construction Cost Guide only includes hard costs.

Below is a portion of the Guide’s page for Private Sector Residential – I only included Toronto and four cities to the West to so that the text in the screen capture is not too tiny to read. Vancouver is slightly more expensive when it comes to construction costs, while the three other cities in the Prairies are all roughly the same, and are considerably less expensive than Toronto or Vancouver.

In Toronto, condo buildings under 12 storeys cost $285 to $390 per square foot. Meanwhile, for buildings over 60 storeys, the average cost is $365 to $490 per square foot, an increase of between 25% to 28% over the shorter buildings. Remember, these are averages over the entire building, and the marginal cost of each extra floor on top is higher than these averages.

Altus also shows a “Premium for High Quality” of another $245 per square foot – so, buildings aimed at the globetrotting elites and foreign investors cost even more. The tallest buildings over 60 storeys tend to be marketed as luxury buildings.

Buildings of six storeys or more tend to be built of poured concrete in Toronto, or sometimes a mix of poured concrete cores and steel frame. But low-rise buildings tend to be wood frame.

Altus shows typical developer built single detached homes at $210 per square foot to $285 per square foot. So, even a condo or 12 storeys or less costs around 35% or more than a detached home, ignoring land and the other parts of the final price.

At a range of $205 per square foot to $250 per square foot, row housing is slightly cheaper to build than detached homes, but row housing has fallen out of favour, as have semi-detached homes. Stacked townhouses (assuming three storeys) actually cost more to build per square foot than the low end of detached housing. However, higher end stacked townhouses are cheaper than the high end of detached houses, since luxury stacked townhomes are not really marketable.

Altus also includes costs for custom built single family residential homes, what might be referred to as “monster homes” when built in existing neighbourhoods. These range from $425 per square foot to a whopping $1,025 per square foot. These are not really relevant to this analysis – beyond the fact that demolishing existing older homes for expensive new ones, adding more square feet but not necessarily more people occupying a property, is hardly the kind of densification that increases supply or improves affordability.

Government costs, like permits and development charges, tent to be constant, or are based on the number of units and bedrooms instead of square feet – smaller units tend to pay more per square foot than large luxury units. How soft costs vary with density is a complicated subject – I recommend this website for a closer look at the costs of building in Toronto.

Yet one soft cost does vary with height or density – financing. The more expensive a building, and the longer it takes from the start of construction until the buyers take possession and pay the developer, the more interest charges will accumulate for each square foot.

Detached homes take roughly ten months to build from start to finish, though preparing the lot (roads, sewers, water, power, etc.) is not included. This little chart below shows the difference in the length of construction by dwelling type. Condo apartments average around two years, and 60+ storey condos would take much longer still. Worse, the time to build anything in Canada has roughly doubled in the last 30 years.

Lastly, we come to the key issue of land price. Detached homes obviously use more land per unit than a condo with a similar number of bedrooms, though condos tend to have far less space and fewer bedrooms than detached homes or even semi-detached ones.

Dense condos use less land per unit, but the land itself is more expensive for each square foot (or square meter) of land. Meanwhile, suburban sprawl might consume more land, but it is cheaper land on the urban fringe.

There is a trade-off here, but ultimately the cost of land for development is a “residual” cost based on the expectations of future profits adjusted for time, risk, and the effort needed to bring a development to completion. This is based on what people will pay, and to some extent, the supply of land and competing development, as well as the value of land for purposes other than redevelopment.

In other words, housing prices are ultimately set by supply and demand. But, excluding land costs (which are only a third of the cost of a condo), the underlying hard and soft costs for a development actually get higher with density and height, not lower!

All content on this website is copyrighted, and cannot be republished or reproduced without permission.

Share this article!

The truth does not fear investigation.

You can help support Dominion Review!

Dominion Review is entirely funded by readers. I am proud to publish hard-hitting columns and in-depth journalism with no paywall, no government grants, and no deference to political correctness and prevailing orthodoxies. If you appreciate this publication and want to help it grow and provide novel and dissenting perspectives to more Canadians, consider subscribing on Patreon for $5/month.

- Riley Donovan, editor