Today, the Kinsol Trestle that spans the Koksilah River is considered to be one of Vancouver Island’s greatest tourist attractions and one of the “most spectacular timber rail trestle structures in the world”.

Fifteen years ago, the former Canadian National Railway span at Mile 53.3 was in a semi-derelict state. After 20 years of abandonment and two attempts by arsonists, it was closed to hikers, cyclists, and equestrians using what had become part of the popular Trans Canada Trail.

Plans for its demolition and replacement with a down-scaled imitation were shelved by public protest that included a petition bearing thousands of names being presented in the provincial legislature (the B.C. Ministry of Transport ‘owns’ the historic railway grade and the Cowichan Valley Regional District manages that section which lies within their domain.)

Ultimately, with the promise of funding from the Ministry and other sources, the CVRD accepted a proposal by a renowned local timber framing firm to “rehabilitate” the Kinsol and, at a total cost of $5.7 million, it was opened to the public with great fanfare in 2011.

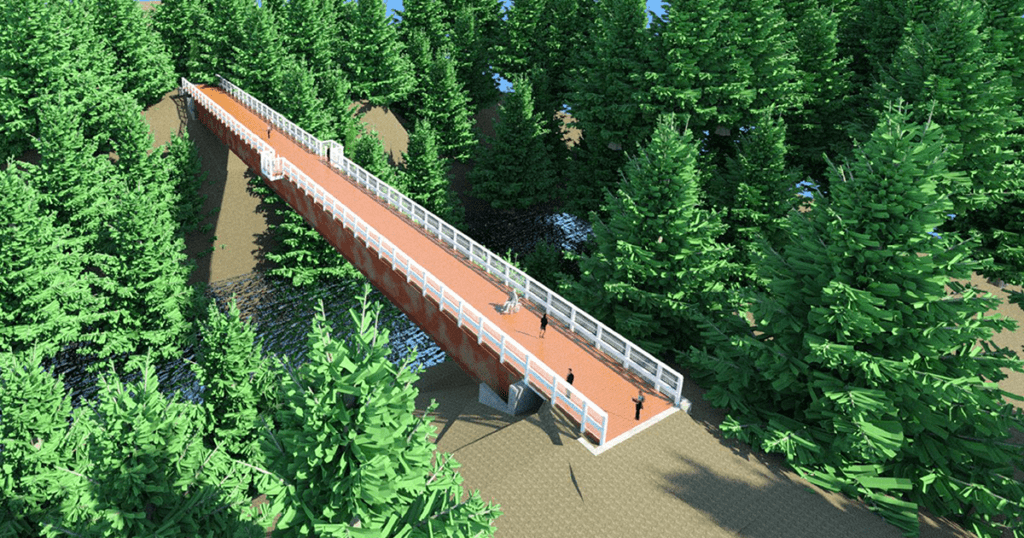

Today, it’s the historically significant Holt Creek Trestle at Mile 59.7 that’s threatened with demolition. Smaller, at 34 metres high and 73 metres long vs. the Kinsol’s 44 metres high and 187 metres long, it is slated to be replaced with a single-span steel bridge with a wooden deck.

Holt Creek has had two major renovations, in 2002 and 2018, and is, according to the Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure, “nearing the end of its lifespan.” The assessment recommended the bridge be replaced rather than continuously repaired and maintained. The decision to demolish is based upon “functionality, constructability, avoiding in-stream works, as well as cost and ease of long-term maintenance”.

If I can’t argue against the trestle’s condition on practical grounds, I can protest the planned replacement. It’s going to look exactly like what it’s intended to be – functional and cost-effective – but no more and no less, even with the two fake bump-outs for viewing (which were for water barrels in the railway days).

Where’s the history in that? Where’s the story of the Canadian National (originally the Canadian Northern Pacific) Railway, which was meant to go from Sidney to Prince Rupert via Seymour Narrows by using the infamous Ripple Rock to cross to the Mainland? Other than some signs with historic photos, and the Kinsol Trestle, the former railway grade is a gravelled pathway.

And, speaking of replacing rather than “continuously” repairing and maintaining the Holt Creek Trestle, is this the long-term future of the Kinsol? Is the day coming when bureaucrats in Victoria crunch the numbers and opt for a steel and concrete crossing for the Koksilah River? Just as almost happened, 20 years ago?

As popular Cowichan Valley blogger Larry Pynn (www.sixmountains.ca) has pointed out, the famous Myra Creek Canyon wooden trestles of the Okanagan’s Kettle Valley Railway that were destroyed by fire in 2003 were rebuilt by the federal government at the cost of $17 million. It should be noted that the wooden Myra Creek trestles were replicated as wooden trestles, not simply replaced with steel and concrete.

I can’t imagine the Kinsol Trestle as just a steel and concrete bridge, as just a means of getting across the Koksilah River. The Trans Canada Trail would become a purely recreational corridor for hikers, cyclists, and equestrians (motorized vehicles are forbidden), with a few attractive signboards thrown in to hint at its railway provenance.

Today, the Kinsol Trestle draws 100,000 visitors annually, and over 78,000 a year visit the Glenora Trails Head Park which is five minutes from Holt Creek. If the century-old Holt Creek Trestle needs to be replaced, it should be rebuilt with timbers to maintain its historical provenance and appearance. Recreational traffic doesn’t require the structural strength necessary for rail traffic.

“The Trans Canada Trail is meant to be more than a recreational corridor—it’s meant to be a step back into history with a story to tell.”

Wooden trestles, I would point out, are a work of genius – designed to be repaired, piece-meal, on a regular basis, particularly in the age before timbers were treated with preservatives to extend their serviceable lifespan. Spans and stringers can be repaired and/or replaced fairly easily, no matter where they’re situated within the structure.

Asked by Larry Pynn as to the true state of the Holt Creek span, Gord Macdonald of the timber framing team that returned the Kinsol to vibrant life, and who worked on Holt Creek’s last structural assessment, said previous unsympathetic repairs have irredeemably altered it. Conceding that continuing to repair it or rebuilding it to its original specifications are the more expensive choices, he noted that a lighter timber structure such as those built on the Myra Canyon line is his preferred option.

At least this version would retain the historical look of a railway trestle. A compromise, yes, as at Myra Canyon (as was, to a lesser degree, the Kinsol) but the Trans Canada Trail is meant to be more than a recreational corridor – it’s meant to be a step back into history with a story to tell. With today’s pressure-treated timbers, the Holt Creek Trestle can maintain its ‘authentic’ look and go on for years and years with minimal maintenance.

Without these wooden trestles – the last men standing of the golden age of logging rail traffic – the Trans Canada Trail is a scenic gravel lane through the countryside. A spokesperson for Associated Engineering, which made the 2018 assessment for the MoT, placed the surviving trestles in their historical context by describing them as being “among the few remaining examples of significant engineering works associated with the early 20th century transportation history of Vancouver Island.”

Timber framing expert Gord Macdonald points out that the value of trestle bridges extends beyond aesthetics and heritage: “When they are maintained, they have economic and tourism value. They’re not just pretty things. They actually help drive the economy.”

“Our collective history is worth more than just dollars and our governments need to actively safeguard it – even if, sometimes, it costs more.”

I’m sure that all of the contracts have been signed and the materials ordered, as work is scheduled to be completed in May 2025. I certainly don’t envision any kind of public protest such as saved the Kinsol. For a dozen reasons, the Kinsol Trestle has more resonance with the general public, even those who’ve never seen it firsthand, than Holt Creek.

What can we take from this?

For one, the opportunity for public consultation was limited to a Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure ‘Information Bulletin’ in late March 2023. Input wasn’t sought: “The new bridge will give recreational trail users an accessible connection between Duncan and Lake Cowichan, enhancing the trail as a transportation corridor and a tourist attraction.”

While acknowledging that “The Holt Creek Bridge is an important active transportation corridor and recreation tourism attraction in the Cowichan Valley,” the decision appears to have been made purely on practical and economic grounds: “The bridge is designed to be functional, durable, and attractive while also being easy to maintain.”

In other words, the century-old wooden Holt Creek Trestle’s historical significance didn’t count for a row of beans. This, despite proven statistical evidence of the value of history and heritage to tourism (never mind other cultural considerations).

Our collective history is worth more than just dollars and our governments need to actively safeguard it – even if, sometimes, it costs more.

All content on this website is copyrighted, and cannot be republished or reproduced without permission.

Share this article!

The truth does not fear investigation.

You can help support Dominion Review!

Dominion Review is entirely funded by readers. I am proud to publish hard-hitting columns and in-depth journalism with no paywall, no government grants, and no deference to political correctness and prevailing orthodoxies. If you appreciate this publication and want to help it grow and provide novel and dissenting perspectives to more Canadians, consider subscribing on Patreon for $5/month.

- Riley Donovan, editor