I just got a 3-month free subscription to Apple TV after a few years away from having it. After watching the last season of Ted Lasso, the next thing I watched was Masters of the Air. It is the follow up series to “Band of Brothers” and “The Pacific”, and follows the actual experiences of US troops from the ”Greatest Generation” in World War 2, though it is not quite as good as the earlier series.

The US bombed Europe during the day and the bomber crews had the highest death rate of any US service. However, my favourite scene was when, after a mission where many planes were shot down and their friends died, the surviving crews sat around and blamed previous generations for the failures of the treaty of Versailles, the Depression, and Britain and France’s failure to stop Hitler.

Of course I made that last part up. My mother was born in England and even served in the Royal Navy herself, and I grew up in the 60s surrounded by people born in the UK or Canada who served or lived through those terrible times of depression and war. My father supposedly got into medical school at U of T but couldn’t afford it. I knew Jews who escaped Germany. I don’t recall my mother or anyone else of that generation blaming the generations before them, though of course we sometimes spoke of history and the events that caused them to live through tough times.

In the 1960s, there was a generational divide between the Boomers and their parents, the whole “don’t trust anyone over 30” thing that was part of the sitcom “All in the Family” in 1971. But it was more of a cultural shift than outright blame, as issues like the Cold War, Vietnam, pollution, and civil rights came to the fore and morality around sex and drugs in particular shifted. In fact, many of the Greatest Generation also questioned the same things, and often it was members of the “Silent Generation” (1928-1945) who led in creating change or conflict. The Beatles and Stones were not Boomers, though the later Punk Rock era bands were.

I love old and classic cars. But there is a term for the cars from around 1973 to the early 1980s as being from the “Malaise Era” of stagflation – the combination of high unemployment, inflation, and huge government deficits that came after the golden years of the 1950s and 1960s. The term “Malaise” is associated with the Presidency of Jimmy Carter and an uninspiring speech he gave on the bad economic conditions, though he never actually used that word.

I don’t recall any Boomers during those times, including me, claiming that the “Malaise” was because the Greatest Generation or the Silents were to blame and didn’t want younger people to prosper as they had.

So, it is very strange to see someone like Eric Lombardi over at The Hub stating “Baby boomers have won the generational war. Was it worth young Canadians’ future?”.

First off, if Boomers or earlier generations failed, it was probably in not teaching subsequent generations enough history – certainly Lombardi seems to lack knowledge about how previous generations went through tough economic times when home ownership seemed impossible. Around 1981, mortgages rates were in the double digits. In Canada, the 1990s were dismal and home construction plummeted – the term “brain drain” was frequently in the news as young people flocked to the US given the lack of jobs here. Boomers went through longer periods of double-digit inflation and/or unemployment, whereas we had a brief period of double-digit unemployment in the pandemic, with low inflation (or deflation). This was followed by the opposite, a brief period of high inflation, but low unemployment.

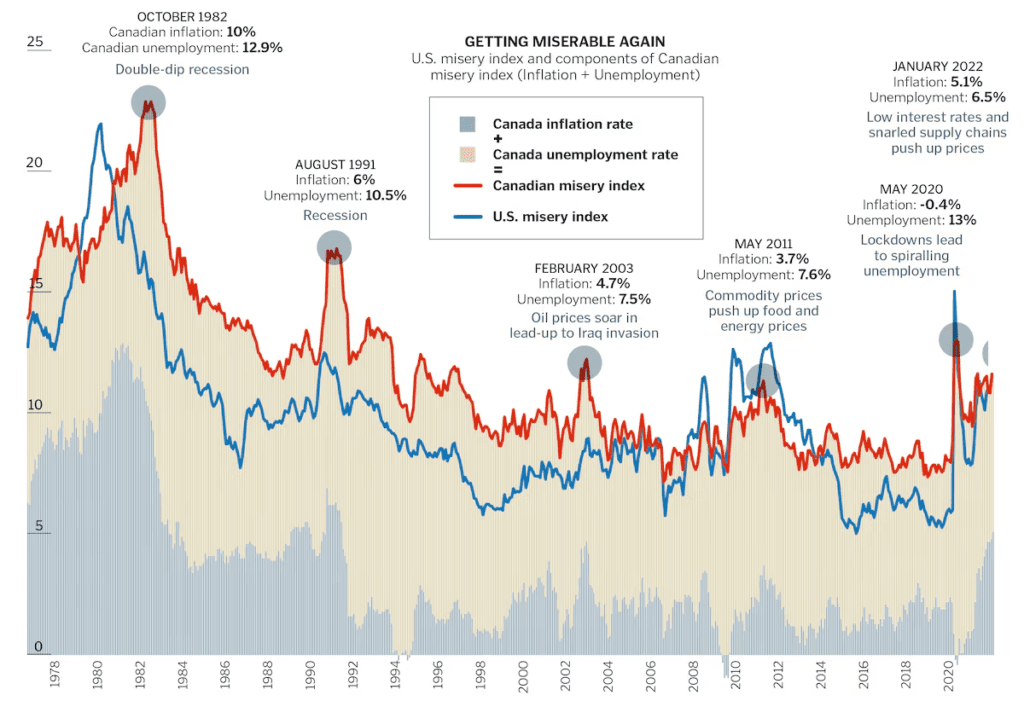

Someone in the 1970s came up with the term “Misery Index”. This is what you get when you simply add the unemployment rate and the inflation rate together. This tends to over-estimate the impact of inflation – in the Depression, the unemployment rate hit around 25% in the US, while many countries have experienced inflation rates of over 1,000%.

The Canadian Misery Index hit 22.9% in October 1982, then 16.5% in August 1991, and 12.2% in February 2003. Since then, it was only higher around May 2020 when it reached 12.6% because of 13% unemployment – but in that period, most people out of work were getting CERB. The Misery Index in Canada is now around 9.0% – 6.1% unemployment plus 2.9% inflation. Canada’s unemployment rate was never below 6% from 1974 to 2018. Inflation was never below 4% annually from 1972 to 1991.

Ignoring the fact that Gen Xers and Millennials stand to eventually inherit the wealth of the older generations, it is unclear what exactly Boomers did to pass the buck to younger people.

In 1996, Boomers were about a third of Canada’s population. Zoning bylaws and most planning policies in Toronto and most other Canadian cities were in place by the early 1970s. Not a great deal was done to discourage construction, except when the Bank of Canada raised interest rates. The neoliberalism of Reagan and Thatcher, combined with high deficits, did lead to governments in the West getting out of building “affordable” or subsidized housing by the mid 1990s – though unlike the UK, we did not privatize the existing stock of units.

In the last few decades, provincial governments have introduced laws to reduce urban sprawl and protect farmland. This limits the supply of land and means densification has become the preferred policy. Even Lombardi isn’t calling for abolishing such restrictions, and Doug Ford got into huge trouble by breaking his promise to protect the Greenbelt (made worse by the way some parcels were to be sold to developers with an inside track from political connections). So, interventionist anti-sprawl policies are accepted and not treated as part of the problem – even though in the American Sunbelt the cities that have both population growth and reasonable housing costs are the ones that don’t restrict sprawl.

Pollution is certainly an issue where future generations lose out from the short sightedness of the earlier generations, but Boomers helped lead the charge against air and water pollution since Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring” was published in the 1960s. The failure of governments in Canada, the US and nearly every other country to take meaningful and significant action since Al Gore’s 2006 movie “An Inconvenient Truth” made global warming a major issue isn’t just the fault of any one generation. Anyone who was 18 in the 2006 election could have done more, and it means that all voters today aged 21 to 36 also share the blame. The next federal election will likely mean that even the Carbon Tax will be eliminated – with no real alternative policy on offer. We are all hypocrites on pollution, not just Boomers.

Setting aside pollution, what exactly did Boomers do on economic and housing issues that was blind to the needs of subsequent generations?

On pensions and healthcare funding, the current social safety net (OAS, CPP, EI, Medicare) was mostly in place by 1973, if not by 1968, when few voters could vote. I will briefly note that the voting age was reduced to 18 from 21 in 1970 thanks to Boomers pushing for it (and Boomers deserve some thanks for that). Those pension and healthcare programs started entirely as “pay as you go” programs – though CPP now is partly funded (thanks to Boomers and others paying towards this).

Canada has a long history of young people moving south to the US for higher incomes or better opportunities – particularly from 1867 to 1900, and then again in the 1990s. But what is the “root cause” of this new malaise? Where is the smoking gun, or the other forensic evidence?

Lombardi states it is not that the younger generations have an overblown sense of entitlement, but rather that:

“To come of age in Canada over recent decades means having borne witness to a steady erosion of your future prospects, with society placing anxiety-inducing burdens that the dominant generation has voted to make your problem. The ugly reality is that younger Canadians are living in the aftermath of a transformation that has eroded the social contract between generations. We have seen nearly every system and institution become a pyramid scheme with the young at the bottom.

…it’s about how Boomers have set policy traps that have systematically kneecapped future generations’ prospects. In their wake, Boomers have now left behind a country of systems littered with economic landmines and lower living standards.”

Lombardi is a YIMBY (“Yes In My Backyard”) who seems to think NIMBYism (“Not In My Backyard”) is a major problem and the solution is generally deregulation or other neoliberal economic policies. He blames the current Trudeau and Ford governments, and “gatekeepers”, for housing policies that don’t create enough supply. This despite the fact that Trudeau is not a Boomer himself, and both governments have only been in power since 2015 and 2018, respectively.

So, where are these landmines and boobytraps left behind by the Boomers?

Well, if we are talking in terms of “decades”, and referring to an erosion of the social contract, then neoliberalism would seem to be the obvious villain. The culprits would be the Mulroney and Chretien governments (1984-1993 and 1993-2003, respectively). All the Boomers had reached the voting age of 18 by 1982, and the first Millennials could not vote until around 1999, so we have had 25 years for younger generations to undo what was done before that is against the interests of Millennials and Gen Xers – who could vote even before 1999.

So, setting aside pollution and the zoning/planning issue, the economic problems are essentially student debt, low incomes, underemployment, unaffordable housing, and paying taxes that mostly support healthcare and income transfers to seniors.

One thing Canada has not done, but that other countries have done, is to raise the age of retirement. In the U.S., the law was changed under Reagan to raise the age to 67, but didn’t come fully into effect until 2022. In fact, Harper did raise the age to 67 with little notice, but then Trudeau reversed it. One way or another, younger people will pay by working 2 more years or getting lower benefits when they retire, but this is unavoidable. Even massively increasing immigration will not make a huge difference, though we actually have increased population growth far above the growth projections done under Harper.

Mulroney enacted a number of major changes as Prime Minister: GST, FTA, negotiating NAFTA, privatizing Crown corporations, reducing screening of foreign direct investment, and then a massive shift in immigration policy. Deficits grew massively under his leadership due to high interest rates (monetarist policy and high inflation) and because the high unemployment and inflation were seen as unusual and likely temporary after the 1950s and 60s. But the debt incurred is only a small part of current federal debt, which ballooned under Harper (2009 crisis) and Trudeau. And of course, the Chretien governments, with Paul Martin as Finance Minister, slashed spending and started to both cut taxes and pay down some of the debt – while only undoing a few of the spending cuts or changes done to get federal spending under control.

The only policies from the Mulroney and Chretien eras that might be to blame for the tough economic conditions experienced by younger generations in Canada today are immigration and trade/investment policies. Yet, there is no movement by young people to change either.

Harper and Justin Trudeau have continued to sign more free trade deals, though Trump demanded and got changes to NAFTA. Lombardi, and other young people on both the left and the right, seem to be content with current trade policy instead of embracing a return to the economic nationalism of Walter Gordon and the NDP Waffle that declined in influence after the 1985 MacDonald Commission Report.

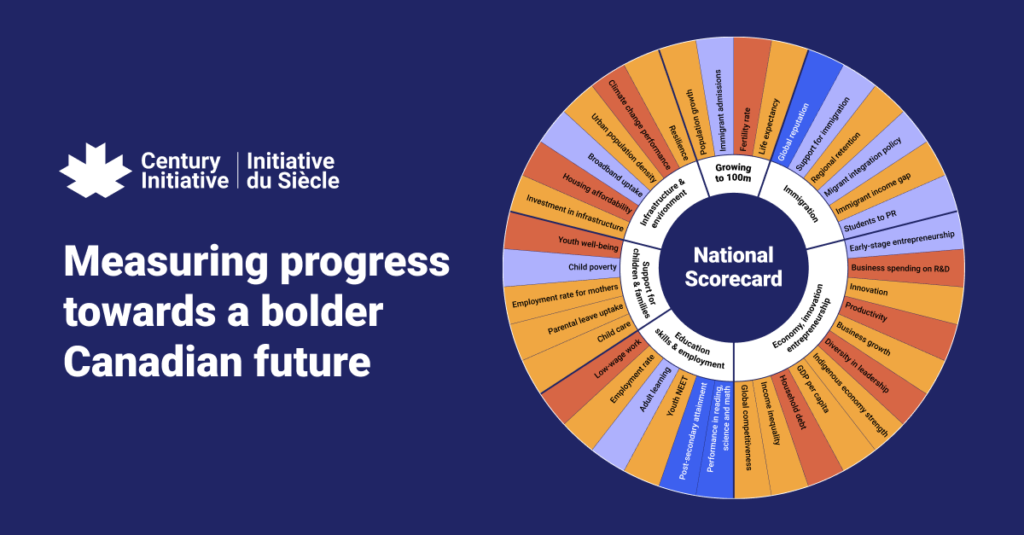

Which leaves immigration, which has been constantly high since the changes in 1990 under Mulroney, but which has gone through the roof under Justin Trudeau since 2015 – seemingly following the plan of the corporate funded Century Initiative for Canada to have 500,000 immigrants and a population target of 100 million in 2100. The rapid increase in foreign students and temporary workers under Trudeau means population growth has exploded.

Young people on the left support high immigration and tend to see any cuts as being driven by xenophobia and racism, but other than the People’s Party of Canada, there has been no significant political group, movement or media outlet calling for massive permanent cuts to immigration.

Even though the Conservative Party is ahead in the polls, there is no indication of any return to its Reform Party roots in calling for major immigration cuts. The Conservative Party’s messages on immigration are vague and sometimes contradictory – that immigration might be tied to housing or that levels might vary – without ruling out that they could even go higher than current Liberal government policy.

So, it is unclear what landmines or boobytraps have been set, other than high student debt (which is mainly provincial jurisdiction with federal grants, transfers or loans), which is also a problem in the US. Neoliberal economic policy, globalization (instead of economic nationalism), and high immigration are not seen as booby traps by Lombardi or others of his generation who claim that previous generations have declared war on younger generations.

Canada, the US, and other Western governments have highly unpopular incumbent governments that look headed for defeat, even if the economic numbers would have been seen as excellent in previous decades. Paul Krugman and others have written on this disconnect between the numbers and public opinion, and polls tend to show that it is younger people who are most unhappy or discontented.

The American and Canadian dreams of upward mobility seem out of reach, but that has been true in earlier times as well like the late 1970s and early ’80s, or in the 1990s. Merely blaming previous generations is not the answer, and it is not necessarily a matter of rich versus poor either – or the “socialism” of Bernie Sanders and others on the left would have had more impact. Maybe swapping out unpopular incumbent governments for new ones will make things clearer, because those governments clearly are failing to communicate effectively or justify their actions or thereof.

Canada’s problems are not unique. On housing, we have more in common with Australia and its housing problems than with those of the US, where housing is well below 2006 levels. The real problem is laying blame on vaguely defined generational groupings without any real solutions on offer – ones that actually identify clear causes and offer practical steps, even if they challenge sacred cows like immigration policy or ideological preferences on the left or right about how to return to an economy with upward mobility in balance with environmental or other goals.

All content on this website is copyrighted, and cannot be republished or reproduced without permission.

Share this article!

The truth does not fear investigation.

You can help support Dominion Review!

Dominion Review is entirely funded by readers. I am proud to publish hard-hitting columns and in-depth journalism with no paywall, no government grants, and no deference to political correctness and prevailing orthodoxies. If you appreciate this publication and want to help it grow and provide novel and dissenting perspectives to more Canadians, consider subscribing on Patreon for $5/month.

- Riley Donovan, editor